Purple pee or purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS) is a rare occurrence that can provoke significant concern among both patients and medical professionals. It is identifiable through straightforward visual inspection and accompanied by clinical manifestations facilitating quick and appropriate treatment. However, a physician’s lack of awareness may jeopardize patient well-being, potentially leading to unnecessary interventions, increased morbidity, and financial strain. Here, we represent a case exemplifying this unexpected phenomenon and deliberate on its underlying mechanisms and available management strategies.

Introduction to Purple Pee Syndrome

Purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS) is an infrequent clinical manifestation encountered by physicians on rare occasions. It represents a peculiar but generally harmless clinical syndrome where a patient’s urinary catheter bag displays purple-colored urine [1]. It results from bacteriuria, whether asymptomatic or causing urinary tract infection (UTI) symptoms, which causes discoloration of the urine seen in a Foley bag. The underlying pathophysiology entails an ongoing bacterial infection wherein specific enzymes generate blue and red-pigmented breakdown products that combine to produce visibly purple urine [2]. Here, we present a rare instance of PUBS observed in an elderly patient with a history of prolonged catheterization and constipation.

Case Presentation

- Patient Background

A 79-year-old female was admitted with the following medical history:- Urinary retention managed with a chronic indwelling Foley catheter

- Recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs)

- Hypertension

- Prior stroke resulting in residual dysarthria and dementia

- Presenting Complaint

- Admitted to the hospital due to altered mental status noticed by family at home.

- The patient was confused but provided a limited history, supplemented by family.

- Symptom Timeline

- The family observed a change in urine color one day before admission.

- The patient became increasingly confused soon after the change.

- The patient expressed discomfort in the lower abdomen.

- Living Situation

- The patient resides at home with family.

- Wheelchair-bound.

- Chronic indwelling Foley catheter due to a history of stroke and neurogenic bladder.

- Physical Examination

- Confused, thin, elderly female in no acute distress.

- Dry mucous membranes.

- Active bowel sounds.

- Tenderness to deep palpation of the lower abdomen.

- Left-sided upper and lower extremity weakness.

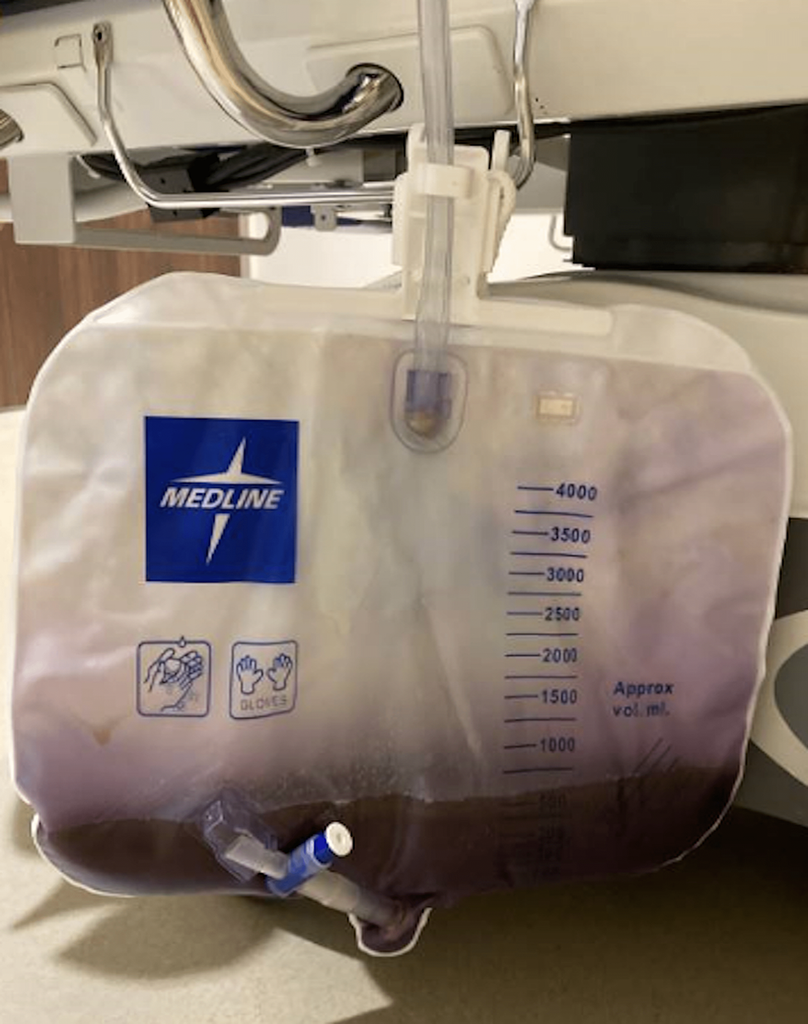

- Foley bag containing purple urine, as exhibited in Figure 1.

- Laboratory Findings

- Significant normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 11 mg/dL.

- Urinalysis revealed cloudy urine positive for nitrites and leukocyte esterase, with over 100 white blood cells per high-power field.

- Imaging

- Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed fluid-filled loops of the small bowel, borderline dilated, suggestive of developing ileus or small bowel obstruction.

Figure 1: The patient’s Foley bag, which displayed purple urine, was present on arrival at the emergency department.

- Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed fluid-filled loops of the small bowel, borderline dilated, suggestive of developing ileus or small bowel obstruction.

- Treatment Initiation

- Empiric antibiotics, including ceftriaxone, were initiated based on prior urine culture data.

- Foley catheter exchanged.

- Intravenous hydration and an aggressive bowel regimen commenced.

- Treatment Outcome

- Within 24 hours of therapy, significant improvement in mentation was observed.

- Within 48 hours, the patient returned to baseline mentation, according to the family.

- Urine color reverted to clear yellow.

- Increased bowel movements and toleration of oral nutrition intake were noted.

- Microbiological Findings: Urine culture positive for Proteus mirabilis and Escherichia coli.

- Antibiotic Course: Completed antibiotic treatment course tailored for complicated UTIs based on culture sensitivities.

- Discharge: The patient was discharged with an outpatient follow-up arranged.

Discussion

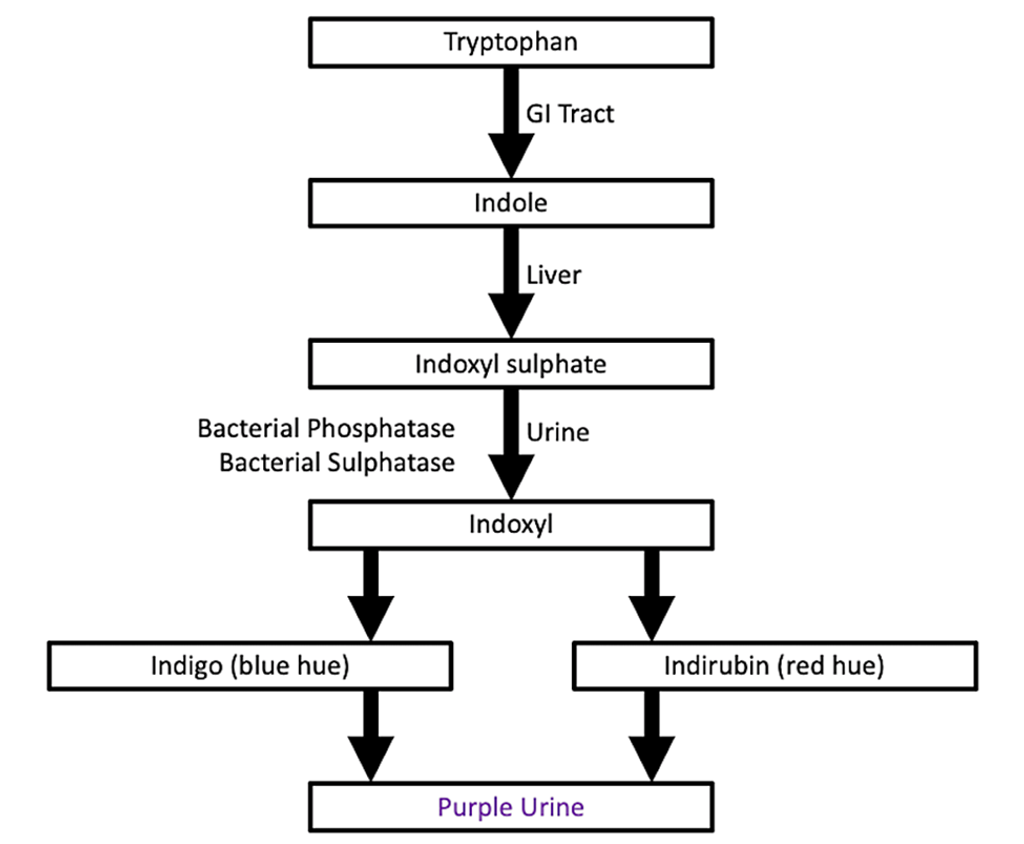

Purple pee syndrome or purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS) arises predominantly as a harmless consequence of bacterial colonization within the urinary tract of patients undergoing chronic urinary catheterization [1]. The purplish hue results from a blend of indirubin, imparting red color and indigo, contributing a blueish shade. When these compounds mingle within the urine, they give rise to the characteristic purple coloration [2]. Both indirubin and indigo originate from the metabolism of tryptophan in the gastrointestinal tract, as depicted in the flowchart illustrated in Figure 2. Tryptophan undergoes metabolic conversion to indole, metabolizing to indoxyl sulfate in the liver. With bacterial assistance, which produces phosphatase and sulphatase, indoxyl sulfate is metabolized to indoxyl in the urine. Under conditions of urine alkalization and dehydration, indoxyl undergoes further transformation into indigo and indirubin [3].

Figure 2: Flowchart illustrating the biochemical pathway resulting in purple urine bag syndrome

PUBS is linked to bacteria capable of creating an alkaline environment, including Providencia, Klebsiella, Proteus, and Enterobacteriaceae [4]. However, purple urine doesn’t automatically signify a urinary tract infection (UTI). Purple urine may appear due to bacterial colonization alone, even in cases of asymptomatic bacteriuria. Distinguishing infectious symptoms can be challenging, particularly as PUBS frequently manifests in elderly patients with dementia, chronic urinary catheters, and associated risk factors such as immobility, constipation, and chronic kidney disease [5,6].

PUBS alone does not mandate treatment. Therapy for PUBS is only warranted if the patient exhibits symptoms associated with the bacteria detected in the urine. The progression of PUBS is usually benign and resolves with urine acidification, either through spontaneous resolution or antibiotic intervention [7]. In symptomatic cases requiring antibiotic treatment, therapy targets the specific organisms identified in urine culture. Understanding the antibiotic susceptibility of these organisms is crucial, given that bacteria causing PUBS often display resistance to multiple antibiotics due to chronic catheterization, the potential for recurrence, and the development of resistance [8].

Prevention stands as the primary approach to addressing PUBS. Preventive measures against catheter-associated UTIs involve minimizing the duration of catheterization whenever feasible. Additionally, clearing blockages in urinary catheters decreases infection risk by ensuring uninterrupted urine flow through the catheter tubing as intended [9]. Two prevalent recommendations to avert UTIs and PUBS entail avoiding prolonged use of indwelling catheters and implementing regular catheter replacements.

Conclusions

PUBS, a rare and harmless condition, arises from bacterial colonization of long-term urinary catheters. It usually signals bacterial overgrowth in the urinary tract, which may or may not provoke symptoms and potential infection. Treatment for PUBS primarily involves observation unless the bacterial strain elicits urinary symptoms, warranting urine analysis, culture, and antibiotic treatment.

References

- Vallejo-Manzur F, Mireles-Cabodevila E, Varon J: Purple urine bag syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2005, 23:521-4. 10.1016/j.ajem.2004.10.006.

- Kumar R, Devi K, Kataria D, Kumar J, Ahmad I: Purple urine bag syndrome: an unusual presentation of urinary tract infection. Cureus. 2021, 13: e16319. 10.7759/cureus.16319

- Popoola M, Hillier M: Purple urine bag syndrome as the primary presenting feature of a urinary tract infection. Cureus. 2022, 14: e23970. 10.7759/cureus.23970

- Shaeriya F, Al Remawy R, Makhdoom A, Alghamdi A, M Shaheen FA: Purple urine bag syndrome. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2021, 32:530-1. 10.4103/1319-2442.335466

- Kalsi DS, Ward J, Lee R, Handa A: Purple urine bag syndrome: a rare spot diagnosis. Dis Markers. 2017, 2017:9131872. 10.1155/2017/9131872

- Yang CJ, Lu PL, Chen TC, Tasi YM, Lien CT, Chong IW, Huang MS: Chronic kidney disease is a potential risk factor for the development of purple urine bag syndrome. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009, 57:1937-8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009. 02445.x

- Lee J: Images in clinical medicine. Purple urine. N Engl J Med. 2007, 357: e14. 10.1056/NEJMicm061573

- Sabir N, Ikram A, Zaman G, Satti L, Gardezi A, Ahmed A, Ahmed P: Bacterial biofilm-based catheter-associated urinary tract infections: causative pathogens and antibiotic resistance. Am J Infect Control. 2017, 45:1101-5. 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.05.009

- Amoozgar B, Garala P, Velmahos VN, Rebba B, Sen S: Unilateral purple urine bag syndrome in an elderly man with nephrostomy. Cureus. 2019, 11: e5435. 10.7759/cureus.5435

About Docquity

If you need more confidence and insights to boost careers in healthcare, expanding the network to other healthcare professionals to practice peer-to-peer learning might be the answer. One way to do it is by joining a social platform for healthcare professionals, such as Docquity.

Docquity is an AI-based state-of-the-art private & secure continual learning network of verified doctors, bringing you real-time knowledge from thousands of doctors worldwide. Today, Docquity has over 400,000 doctors spread across six countries in Asia. Meet experts and trusted peers across Asia where you can safely discuss clinical cases, get up-to-date insights from webinars and research journals, and earn CME/CPD credits through certified courses from Docquity Academy. All with the ease of a mobile app available on Android & iOS platforms!