Sotos syndrome, a congenital disorder, is characterized by prenatal and postnatal overgrowth, varying degrees of mental retardation, accelerated bone development, and distinct craniofacial attributes such as macrocephaly, frontal bossing, and a high hairline. Recent studies have shown that the haploinsufficiency of the NSD1 gene, located at 5q35 and encoding the nuclear receptor binding SET domain-containing protein 1), is responsible for Sotos syndrome. This condition often poses diagnostic challenges due to its resemblance to other undefined overgrowth conditions. Here, we present a rare case of Sotos syndrome, detailing its clinical features and the craniofacial characteristics typically observed in affected individuals.

Introduction on Sotos Syndrome

Sotos syndrome is characterized as a disorder of juvenile overgrowth, with the majority of cases being sporadic. While the features resembling Sotos syndrome were possibly documented as early as 1931, it was formally described by Sotos et al. in 1964 [1,2]. This syndrome has been observed worldwide among various ethnic groups. Cole and Hughes, in 1994, established four primary diagnostic criteria after systematically assessing forty-one classic cases [1,3]. These criteria included macrocephaly, learning difficulties, distinctive facial characteristics, and overgrowth with advanced bone development. These clinical benchmarks served as the foundation for diagnosing Sotos syndrome until 2002. Recently, mutations and deletions of the NSD1 gene, encoding the nuclear receptor binding SET domain-containing protein 1, have been identified in these cases [4]. This discovery has prompted a reassessment of the syndrome’s features. However, up to thirty-five percent of reported cases of Sotos syndrome have shown no NSD1 abnormalities. In such instances, the involvement of NSD2 and NSD3 genes has been ruled out through sequencing [5].

Previously recognized as “cerebral gigantism,” Sotos Syndrome exhibits considerable variability among cases, yet its classic phenotype ranks as one of the most prevalent overgrowth conditions, possibly second only to Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome [6,7]. Craniofacial anomalies characteristic of this syndrome includes a broad forehead, elevated hairline, macrocephaly, downward-slanting palpebral fissures, mild micrognathia, and a pointed chin. Patients also commonly present with renal abnormalities, cardiac anomalies, seizures, and scoliosis, varying in severity [8,9]. Intellectual and psychomotor development levels vary, with some individuals exhibiting no mental retardation while others experience severe cases. Developmental delays manifest in a spectrum of learning disabilities, clumsiness, autistic features, adaptive issues, hyperactivity disorders, and attention deficits. Neuroimaging findings typically lack specificity, with hypoplasia of the corpus callosum and ventricular dilatation commonly observed [10]. Additionally, individuals with Sotos syndrome face a heightened risk of both benign and malignant tumors.

Case Presentation

Patient Information

- A four-year-old boy presented to the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology with his parents, reporting multiple decayed teeth over the past year.

Clinical History

- According to the patient’s uncle, the child experienced swelling and pain on the right side of his face a few months ago, followed by progressive tooth fracturing for several months.

- Previously treated at a dental hospital for a right buccal space infection, the child underwent extraction of severely decayed teeth under general anesthesia, with an uneventful post-extraction period.

Medical Background

- The child has a confirmed diagnosis of Sotos syndrome, born to non-consanguineously married parents following four years of infertility treatment.

- Born at term with a birth weight of 2.2 kg, the child’s prenatal and birth history were unremarkable, except for jaundice on the fourth day, requiring three days of phototherapy.

- Surgical interventions included right inguinal herniotomy at one month and left orchidopexy at one year of age.

- At one year old, the child experienced seizures treated with valparin, discontinued after four months due to tooth discoloration and chipping.

Family History

- The child is the only offspring of the parents, with no other family members affected by Sotos syndrome.

- Parents reported delayed milestones in walking and speech, poor concentration, and delayed mental development.

- Additionally, feeding difficulties, recurrent fevers, and rapid agitation were noted by the parents.

General and Extraoral Examination

Fig 1. Clinical photograph showing macro dolichocephaly.

Fig 2. Clinical photograph showing frontal bossing.

- The patient exhibited macro dolichocephaly (Fig 1), frontal bossing (Fig 2), and typical dysmorphic facies, including an elongated face and receding hairline.

Fig 3. Clinical photograph showing typical dysmorphic facies, elongated face, receding hairline, sparse eyebrows, low set large ears, apparent ocular hypertelorism with down slanting palpebral fissures, sunken eyes, bilateral divergent squint, depressed nasal bridge, prominent jaw, malar flushing, mild micrognathia.

- Additional facial features comprised sparse eyebrows, low-set large ears, apparent ocular hypertelorism with down slanting palpebral fissures, sunken eyes, bilateral divergent squint, a depressed nasal bridge, prominent jaw, malar flushing, and mild micrognathia (Fig 1, Fig 2, and Fig 3).

- Generalized hypotonia was observed, along with a blind sinus in the sacral region, with no other cranial nerve deficits noted.

Intraoral Examination

- Examination within the oral cavity revealed a high-arched palate, multiple missing teeth, and severely decayed and fractured teeth.

- The presence of deposits and high caries activity suggested poor oral hygiene.

- The patient exhibited non-cooperation for both radiographs and intraoral photographs.

Radiographic Examination

- Extraoral radiographs were attempted, revealing a prominent forehead (Fig 4) and many missing teeth, with only a few tooth buds visible (Fig 5), suggesting extraction or congenital absence.

Fig 4. Extraoral radiograph showing prominent forehead.

Fig 5. An extraoral radiograph revealed the absence of a significant number of his teeth, and very few tooth buds were visible.

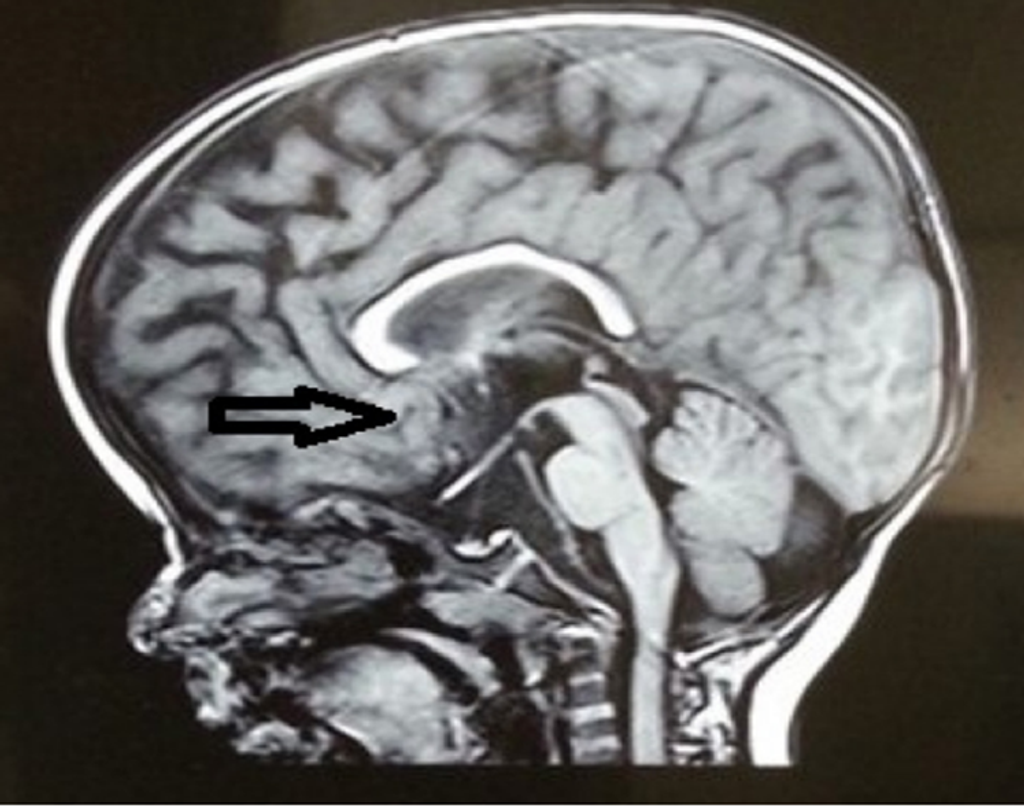

Fig 6. MRI revealing cortical displacement. The indentations are more than what is usually present in a child of age 3-4 years

- MRI findings indicated cortical displacement, with indentations exceeding typical levels for a child aged 3-4 years (Fig 6), along with decreased periventricular white matter (Fig 7). However, the corpus callosum appeared to be of normal size (Fig 8).

Fig 7. MRI showing decreased periventricular white matter

Fig 8. MRI showing Corpus callosum of apparently normal size

- Following these findings, the patient was referred to a pediatrician and craniofacial surgeon for further evaluation, confirming the clinical features and extraoral findings.

- The parents were provided with oral hygiene instructions and dietary counseling, and they were subsequently referred to the Department of Pedodontics for necessary interventions.

- Restorative/rehabilitative treatments are ongoing through scheduled appointments.

Discussion

For the past forty years, the diagnosis of Sotos syndrome has primarily relied on the subjective assessment of clinical features. While the craniofacial characteristics of this syndrome are distinctive, other aspects lack specificity. Discussions on these cases have often revolved around the absence of specific clinical features [2,11,12]. Generally, pregnancies involving Sotos syndrome are considered normal, although instances of pre-eclampsia or toxemia may be documented [2,12]. Infants with Sotos syndrome tend to be larger than average for their gestational age despite their mean gestational age being around 39 weeks. According to Cole and Hughes, measurements such as length at birth, weight at birth, and occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) typically deviate by 3.2, 1, and 1.8 standard deviations above the mean, respectively. Additionally, Tatton-Brown reported that approximately 76 percent of the 107 cases of Sotos syndrome had infants with birth weights below the 98th percentile [2,13].

Many infants encounter difficulties with early feeding, with some necessitating tube feeding. Additionally, they may exhibit varying degrees of congenital hypotonia and can develop jaundice due to hyperbilirubinemia or hypoglycemia. Growth acceleration is particularly notable in the first year of life, stabilizing between two and six years of age. Height and weight typically normalize during puberty, attributed to the fusion of epiphyses. Final height often falls within the high normal range, especially in females, as growth patterns correlate with advanced bone age and early puberty onset. Consistent features of this syndrome include macrocephaly, large hands, and large feet. Craniosynostosis has been documented in some cases, evidenced by premature fusion of coronal, sagittal, and lambdoid sutures [2].

Between the ages of one and six, characteristic features are prominent. Infants typically exhibit a round face with a disproportionately prominent forehead, which elongates during adolescence, often accompanied by a pronounced pointed chin. Additionally, features such as a receding hairline, macrocephaly, dolichocephaly, micrognathia, hypertelorism, down-slanting palpebral fissures, prominent jaw, malar flushing, anteverted nostrils, large ears, and high-arched palate are commonly observed [2]. In our case, at four years of age, additional features, including an elongated face, sparse eyebrows, low-set large ears, sunken eyes, bilateral divergent squint, depressed nasal bridge, prominent jaw, malar flushing, and mild micrognathia, were noted.

Neurological dysfunction, typically non-progressive, manifests as reduced coordination and clumsiness. Childhood is marked by language and motor developmental delays, with variable degrees of learning disabilities. Notably, walking is often delayed until around fifteen months, and speech until approximately two and a half years of age. Febrile seizures occur in more than half of affected children [2]. In our case, seizures developed at one year of age, accompanied by delayed walking, speech, and poor concentration abilities. The parents also reported feeding difficulties, recurrent fevers, and the child’s tendency to become agitated quickly.

Other features that may be observed include:

- cerebral ventricle dilation,

- absence of the corpus callosum,

- prominent cortical sulci,

- cavum septum pellucidum, and

- cavum velum interposition

MRI findings revealed cortical displacement and decreased periventricular white matter in this case [2].

Dental care for such children presents significant challenges due to intellectual limitations, poor communication skills, and reduced ability to comprehend dental procedures. Therefore, oral health management primarily emphasizes preventive measures. Their inability to effectively remove plaque increases their susceptibility to dental caries. The parents or guardians of children with special needs must recognize the importance of collaborative efforts between the family and dental professionals to ensure thorough supervision of oral hygiene and improve oral health status [7].

In this case, the patient was referred to a pediatrician and craniofacial surgeon for consultation. The parents received oral hygiene instructions and dietary counseling to facilitate proper care.

Jaundice during the neonatal period, as in our case, can effectively be managed through phototherapy. Modifying baby food textures to facilitate swallowing may be considered. Implementing adaptations such as feeding upright and elevating the head of the bed can help prevent issues like gastroesophageal reflux, heartburn, and vomiting.

Regular follow-up appointments with a pediatrician are crucial to address concerns such as constipation, respiratory infections, seizures, and the heightened risk of future tumor development [2,15]. A comprehensive treatment approach is imperative, including preventive measures, restorations, and extractions, educating and motivating parents to maintain optimal oral hygiene practices, and scheduling periodic dental surgeon visits for checkups.

In our case, we have adopted a comprehensive approach to treatment. Following consultations with the craniofacial surgeon and pediatrician, restorative/rehabilitative therapies are implemented during subsequent appointments [1].

Conclusion

The medical issues, disabilities, and constraints faced by children with special needs pose significant demands and challenges. Unfortunately, the general societal attitude often overlooks the importance of oral health care for these individuals. Parents of such children must understand that neglecting daily oral hygiene can result in dental issues, leading to discomfort, pain, and potential systemic consequences for their children.

Parents play a crucial role in managing the oral health of children with special needs. By educating and motivating both the patient and parents, we can adopt a comprehensive treatment approach that ensures their oral health needs are adequately addressed and managed.

References

- Juneja A, Sultan A. Sotos syndrome. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2011; 29:48-51.

- Baujat G, Cormier-Daire V. Sotos syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007; 2:36.

- Cole TR, Hughes HE. Sotos syndrome: A study of the diagnostic criteria and natural history. J Med Genet. 1994; 31:20-32.

- Kurotaki N, Imaizumi K, Harada N, Masuno M, Kondoh T, Nagai T, et al. Haploinsufficiency of NSD1 causes Sotos syndrome. Nat Genet. 2002; 30:365-6.

- Douglas J, Coleman K, Tatton-Brown K, Hughes HE, Temple IK, Cole TR, et al. Childhood Overgrowth Collaboration: Evaluation of NSD2 and NSD3 in overgrowth syndromes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005; 13:150-3.

- Sotos JE, Dodge PR, Muirhead D, Crawford JD, Talbot NB. Cerebral gigantism in childhood: A syndrome of excessively rapid growth with acromegalic features and a nonprogressive neurologic disorder. N Engl J Med. 1964; 271: 109-16.

- Gomes-Silva JM, Ruviere DB, Segatto RA, De Queiroz, AM, De Freitas AC. Sotos syndrome: A case report. Spec Care Dentist. 2006; 26:257-262.

- Piccione M, Consiglio V, Di Fiore A, Grasso M, Cecconi M, Perroni L, Corsello G. Deletion of NSD1 exon 14 in Sotos syndrome: first description. J Genet. 2011; 90:119-123.

- Leventopoulos G, Kitsiou-Tzeli S, Kritikos K, Psoni S, Mavrou A, Kanavakis E, Fryssira H. A clinical study of Sotos syndrome patients with review of the literature. Pediatric Neurol. 2009; 40:357-364.

- Leventopoulos G, Kitsiou-Tzeli S, Psoni S, Mavrou A, Kanavakis E, Willems P, Fryssira H. Three novel mutations in Greek Sotos patients with rare clinical manifestations. Horm Res. 2009; 71: 45-51.

- Cole TRP, Hughes HE. Sotos syndrome: A study of the diagnostic criteria and natural history. J Med Genet. 1994; 31:20-32.

- Opitz J, Weaver D, Reynolds J. The syndromes of Sotos and Weaver: Reports and Review. Am J Med Genet. 1998; 179:294-304.

- Tatton-Brown K, Rahman N. Clinical features of NSD1-positive Sotos syndrome. Clin Dysmorphol. 2004; 13:199-204.

- Tatton-Brown K, Douglas J, Coleman K, Baujat G, Cole TR, Das S et al. Childhood Overgrowth Collaboration: Genotype-phenotype associations in Sotos syndrome: An analysis of 266 individuals with NSD1 aberrations. Am J Hum Genet. 2005; 77:193-204.

- Adhami EJ, Cancio-Babu CV. Anesthesia in a child with Sotos syndrome. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003; 13:835-840.

About Docquity

If you need more confidence and insights to boost careers in healthcare, expanding the network to other healthcare professionals to practice peer-to-peer learning might be the answer. One way to do it is by joining a social platform for healthcare professionals, such as Docquity.

Docquity is an AI-based state-of-the-art private & secure continual learning network of verified doctors, bringing you real-time knowledge from thousands of doctors worldwide. Today, Docquity has over 400,000 doctors spread across six countries in Asia. Meet experts and trusted peers across Asia where you can safely discuss clinical cases, get up-to-date insights from webinars and research journals, and earn CME/CPD credits through certified courses from Docquity Academy. All with the ease of a mobile app available on Android & iOS platforms!