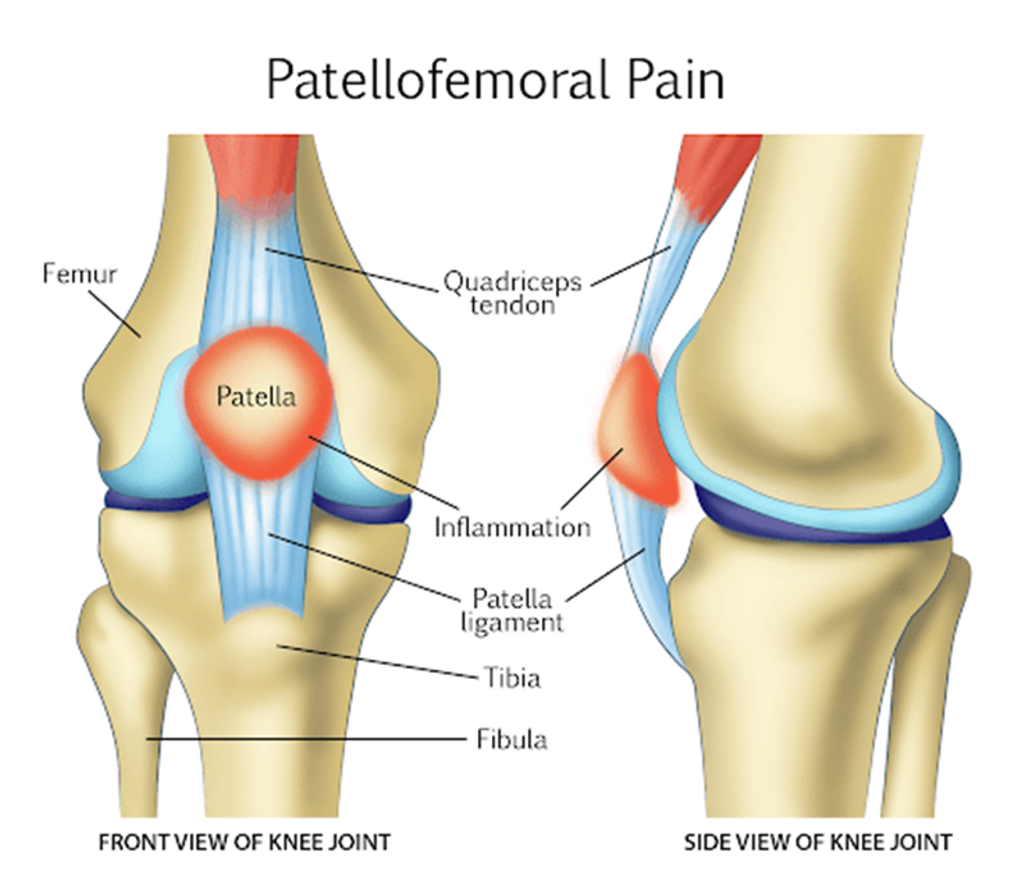

Patellofemoral syndrome (PFS) is a prevalent contributor to anterior knee pain, often recognized by various names such as runner’s knee, patellofemoral pain syndrome, retropatellar pain syndrome, lateral facet compression syndrome, or idiopathic anterior knee pain. It typically emerges as a diagnosis once other intra-articular and peripatellar conditions have been excluded. Pain manifests as it is situated behind or surrounding the patella and worsens with a flexed knee joint loading. Clinically, it ranks among the most frequent causes of knee pain. Research indicates that a considerable portion of patients, up to two-thirds, can achieve successful outcomes through appropriate rehabilitation protocols.

This review aims to underscore the interprofessional team’s collaborative efforts in evaluating and managing patients afflicted with patellofemoral syndrome.

Objectives

- Determine the causes of underlying medical conditions and emergencies associated with patellofemoral syndrome.

- Detail the suitable methods for assessing patellofemoral syndrome.

- Examine the array of treatment choices for managing patellofemoral syndrome.

- Elaborate on interprofessional team tactics to enhance care coordination and communication to progress patellofemoral syndrome treatment and enhance outcomes.

Introduction

Patellofemoral syndrome (PFS), alternatively termed patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) or runner’s knee, represents a prevalent source of anterior knee pain encountered in clinical practice. Patients commonly report diffuse anterior knee pain exacerbated by activities involving a flexed knee, such as running, stair climbing, and squatting. PFS is typically diagnosed after excluding intraarticular or peripatellar pathologies. While most PFS patients respond well to conservative treatments, a small subset may exhibit resistance to therapies, resulting in persistent symptoms over an extended duration.

Etiology: Patellofemoral Syndrome

The exact origins of patellofemoral syndrome lack unanimous consensus; nevertheless, it is likely multifactorial and associated with training methods. It is believed to implicate six anatomical regions, comprising subchondral bone, synovium, retinaculum, skin, nerve, and muscle [1]. Research indicates four primary factors contributing to this syndrome: lower extremity and patellar malalignment, muscular imbalances in the lower extremity, overactivity/overload, and trauma [2]. Among these factors, overuse emerges as particularly significant. Additionally, studies demonstrate that early specialization in sports increases the relative risk of developing PFS by 1.5 times compared to athletes engaged in multiple sports [3].

- Malalignment and Muscular Imbalance

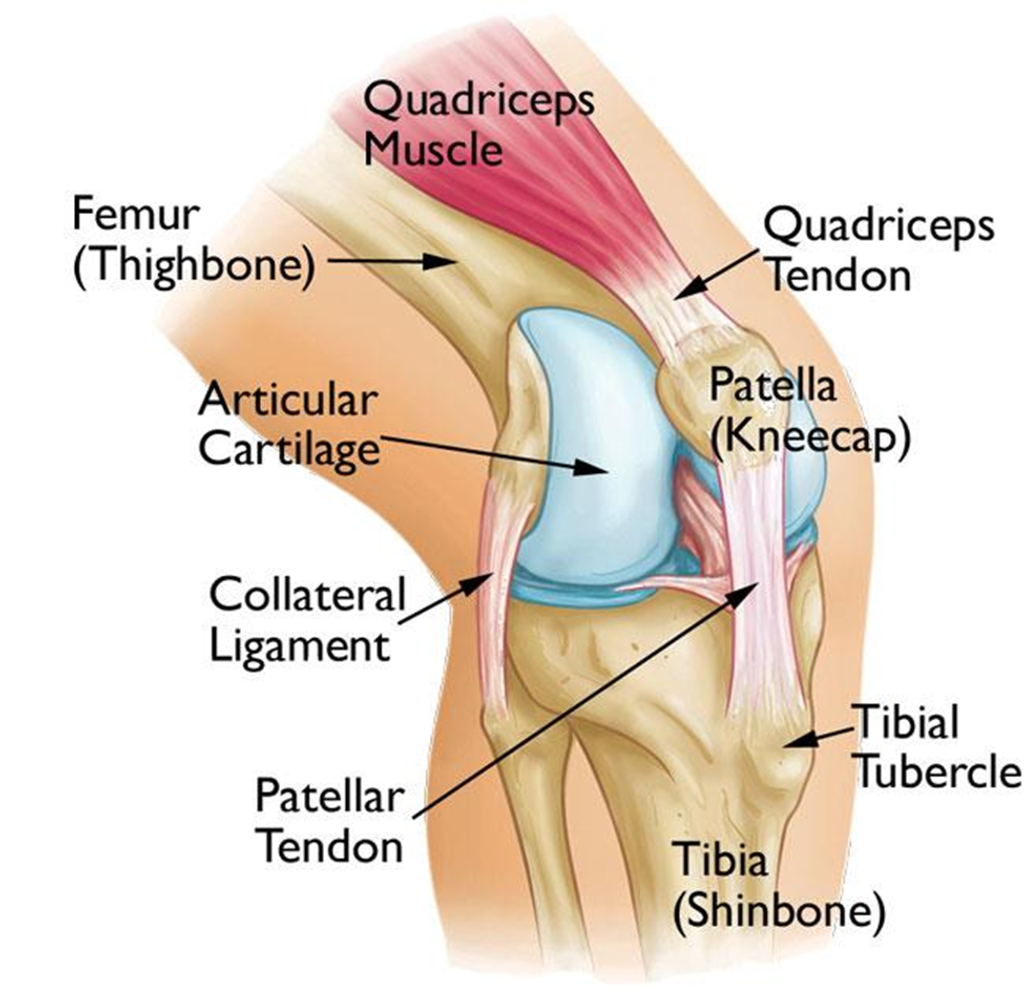

The patellofemoral joint’s functionality relies on a complex interplay between static and dynamic structures encompassing the entire lower extremity as the patella moves within the trochlea. Static elements involve:

- leg length disparities,

- irregular foot anatomy,

- tightness in the hamstring and hip musculature,

- angular or rotational deformities, and

- variations in trochlear morphology

Dynamic factors include muscle weakness, ground reaction forces, and inadequate or excessive foot pronation. Research on malalignment contributing to patellofemoral syndrome (PFS) yields conflicting results, indicative of its multifaceted nature. Several studies suggest that weakness in the hip abductors may be a significant factor [4]. Additionally, findings from a study focusing on female runners identified hip biomechanics as a potential contributor, linking greater hip adduction angles with an elevated risk of developing PFS [5]. While some studies demonstrate an association between hip abductor weakness and PFS, others fail to establish a relationship. In certain cases, increased hip abduction strength has even been implicated as a cause [6].

- Overactivity and Overload

Numerous patients diagnosed with PFS exhibit no discernible signs of malalignment. Rather, thorough interviews often reveal descriptions of overload experienced by the patellofemoral joint, which can precipitate the onset of PFS [7]. Research has demonstrated a correlation between heightened workload on the joint, such as increased mileage or volume of activity, and the development of PFS. Patients frequently report that pain initiates during periods of intensified physical activity [8,9]. Risk factors contributing to overload and consequently escalating the risk of PFS encompass previous fitness levels, exercise routines, and a BMI exceeding 25 [10].

- Trauma

Injuries directly or indirectly affecting the patellar region can damage structures that may lead to PFS.

While studies have identified the causes mentioned above or risks associated with the development of patellofemoral syndrome, it is widely acknowledged that its onset is seldom attributable to a single factor.

Epidemiology

Patellofemoral syndrome ranks among the prevalent knee conditions encountered by clinicians. In active individuals, it may represent approximately 25% to 40% of all knee issues addressed in a sports medicine clinic, although the precise incidence remains uncertain [4]. Studies indicate that PFS disproportionately affects women, with a ratio close to 2:1 compared to men [11,12]. Typically, its onset occurs during adolescence and adulthood, particularly in the second and third decades of life, with a prevalence exceeding 20% during adolescence [13].

History and Physical

The accurate diagnosis of patellofemoral syndrome heavily relies on a comprehensive and precise evaluation of medical history and physical examination. Symptoms may manifest unilaterally or bilaterally and can present gradually or suddenly. Patients often report exacerbation of symptoms during activities such as squatting, running, prolonged sitting, or stair use [14]. The pain is typically vague and poorly localized, commonly described as situated behind or around the patella, and characterized by an achy sensation. However, it can also be perceived as sharp. As PFS is a diagnosis reached by excluding other conditions it may mimic, it is imperative to rule out alternative pathologies. Some patients may report sensations of the knee giving way or catching, indicative of potential ligamentous or intraarticular issues. During patient history-taking, particular emphasis should be placed on inquiries regarding knee trauma, including past surgeries and instances of overuse activities.

A general assessment and observation of the patient and the affected joint will be conducted during the physical examination. Consider factors such as obesity and age. Look for any muscular irregularities, such as potential vastus medialis atrophy. Additionally, inspect the joint for signs of erythema that might indicate infection. Palpation can offer valuable insights, such as assessing tenderness in the quadriceps or patellar tendons and checking for signs of effusion or warmth. Simple muscle strength testing can provide further diagnostic clues, particularly for hip abductors and quadriceps. Note any disparities in strength between the affected and unaffected sides, as patellofemoral syndrome (PFS) may contribute to weakness. Evaluate the range of motion of the affected knee. Lastly, the ipsilateral hip should also be examined as the pain could be referred.

Numerous specialized tests may be conducted, although many lack specificity for identifying PFS. A study comparing the diagnostic accuracy of various clinical indicators found that the sensitivity of tests such as the patellar tilt, active instability, patella alta, and apprehension tests was generally low, around 50%. In comparison, specificity ranged from 72% to 100% [15]. Furthermore, in the same study, individuals with patellofemoral pain syndrome commonly exhibited increased quadriceps angle, lateral and medial retinaculum tenderness, patellofemoral crepitation, squinting patella, and restricted patellar mobility. Additionally, measurements of the popliteal angle are closely linked with the development of patellofemoral syndrome. Popliteal angle measurements are utilized to assess the flexibility of the hamstring muscles. Tight hamstrings exert compressive forces on the patellofemoral joint, increasing the risk of developing PFS [16].

Evaluation

The diagnosis of patellofemoral pain syndrome is primarily clinical. Further investigation through plain radiography is typically not pursued until symptoms persist despite one to two months of conservative management. Radiographs often do not align closely with the reported symptoms, and distinguishing between the affected and unaffected sides can be challenging [15]. If conservative therapy fails to yield improvement, imaging is employed to exclude other potential sources of similar pain, such as bipartite patella, osteoarthritis, loose bodies, and occult fractures. Advanced imaging modalities like MRI, musculoskeletal ultrasound, and CT scans are generally not warranted and are typically reserved for assessing alternative pathologies.

Treatment and Management

Treatment for patellofemoral syndrome typically follows a conservative approach aimed at alleviating pain, enhancing patellar tracking, and restoring previous levels of function. These treatments are usually categorized into two main phases: acute and recovery. During the acute phase, interventions often involve:

- modifying activities,

- using NSAIDs for pain management and

- employing conservative modalities like ice therapy.

Although NSAIDs, particularly naproxen, have demonstrated efficacy in reducing overall pain compared to aspirin and placebo, they are generally not recommended for long-term use [17]. Therapeutic modalities such as ultrasound and electrical stimulation have not significantly improved symptoms [18][19].

Following the acute phase, patients transition to recovery, focusing on addressing underlying issues contributing to the condition’s development. Combining knee and hip exercises to enhance lower extremity strength, mobility, and function is considered the most effective intervention [20]. In cases where patients experience pain during exercises, adjunct therapies such as patellar taping can be utilized. Research indicates that when used alongside physical therapy, patellar taping can reduce overall pain compared to physical therapy alone [21]. However, its effectiveness may be diminished in individuals with higher BMI [22].

Therapeutic approaches should be individualized and tailored to address each patient’s dysfunctions. Referral to orthopedic surgery is generally not recommended and is considered a last-resort treatment option [23]. Non-operative therapy should be pursued for at least 24 months before considering surgical interventions [24].

Differential Diagnosis

As previously mentioned, the range of potential diagnoses for patients presenting with PFS is extensive and can be categorized into six anatomical areas. These encompass conditions such as patellofemoral OA, Osgood Schlatter’s disease, plica-related issues, bursitis (including prepatellar or Hoffa’s), Saphenous neuritis, quadriceps tendinopathy, patellar tendinopathy, or pain referred from the hip or back. Given this wide array of possibilities, the clinician must conduct a comprehensive history and physical examination to identify specific risk factors and ensure appropriate management for the patient.

Prognosis & Complications

The prognosis for patellofemoral syndrome is generally favorable; however, approximately 40% of patients diagnosed with PFS may continue to experience symptoms one year after receiving typical treatment [25]. A seven-year study revealed that nearly 85% of patients treated with a home exercise regimen reported successful outcomes [26]. Factors associated with a poor long-term prognosis include a hypermobile patella, advanced age, and symptoms affecting both knees [26].

Complications of PFS may include the development of patellofemoral osteoarthritis resulting from inadequate patellar tracking, which can lead to persistent pain. Additionally, some patients may be compelled to discontinue activities they previously enjoyed due to the discomfort caused by these activities.

Improving Healthcare Team Performance

The patellofemoral syndrome typically carries a favorable prognosis, but its impact on patients can be significant due to pain-related limitations. An accurate diagnosis of individuals experiencing anterior knee pain hinges on thoroughly understanding their current symptoms. Once diagnosed, healthcare providers must educate patients about treatment timelines and the importance of rest. Physical therapy plays a crucial role in the recovery process and should be initiated promptly as tolerated by the patient. Maintaining open communication with the physical therapist is essential for optimizing patient outcomes. Their input regarding the appropriate timing for the patient’s return to sports or exercise activities is invaluable.

References

- Fulkerson JP. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with patellofemoral pain. Am J Sports Med. 2002 May-Jun;30(3):447-56.

- Thomeé R, Augustsson J, Karlsson J. Patellofemoral pain syndrome: a review of current issues. Sports Med. 1999 Oct;28(4):245-62.

- Hall R, Barber Foss K, Hewett TE, Myer GD. Sport specialization’s association with an increased risk of developing anterior knee pain in adolescent female athletes. J Sport Rehabil. 2015 Feb;24(1):31-5.

- Witvrouw E, Callaghan MJ, Stefanik JJ, Noehren B, Bazett-Jones DM, Willson JD, Earl-Boehm JE, Davis IS, Powers CM, McConnell J, Crossley KM. Patellofemoral pain: consensus statement from the 3rd International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat held in Vancouver, September 2013. Br J Sports Med. 2014 Mar;48(6):411-4.

- Noehren B, Hamill J, Davis I. Prospective evidence for a hip etiology in patellofemoral pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013 Jun;45(6):1120-4.

- Herbst KA, Barber Foss KD, Fader L, Hewett TE, Witvrouw E, Stanfield D, Myer GD. Hip Strength Is Greater in Athletes Who Subsequently Develop Patellofemoral Pain. Am J Sports Med. 2015 Nov;43(11):2747-52.

- Dye SF. The pathophysiology of patellofemoral pain: a tissue homeostasis perspective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005 Jul;(436):100-10.

- Macera CA. Lower extremity injuries in runners. Advances in prediction. Sports Med. 1992 Jan;13(1):50-7.

- Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB, van Poortvliet JA, Phillips H. Mechanical factors in the incidence of knee pain in adolescents and young adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984 Nov;66(5):685-93.

- Hart HF, Barton CJ, Khan KM, Riel H, Crossley KM. Is body mass index associated with patellofemoral pain and patellofemoral osteoarthritis? A systematic review, meta-regression, and analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017 May;51(10):781-790.

- DeHaven KE, Lintner DM. Athletic injuries: comparison by age, sport, and gender. Am J Sports Med. 1986 May-Jun;14(3):218-24.

- Taunton JE, Ryan MB, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Lloyd-Smith DR, Zumbo BD. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2002 Apr;36(2):95-101.

- Tállay A, Kynsburg A, Tóth S, Szendi P, Pavlik A, Balogh E, Halasi T, Berkes I. [Prevalence of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Evaluation of the role of biomechanical malalignments and sports activity]. Orv Hetil. 2004 Oct 10;145(41):2093-101.

- Post WR. Clinical evaluation of patients with patellofemoral disorders. Arthroscopy. 1999 Nov-Dec;15(8):841-51.

- Haim A, Yaniv M, Dekel S, Amir H. Patellofemoral pain syndrome: validity of clinical and radiological features. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006 Oct;451:223-8.

- Whyte EF, Moran K, Shortt CP, Marshall B. The influence of reduced hamstring length on patellofemoral joint stress during squatting in healthy male adults. Gait Posture. 2010 Jan;31(1):47-51.

- Heintjes E, Berger MY, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Bernsen RM, Verhaar JA, Koes BW. Pharmacotherapy for patellofemoral pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2004(3):CD003470.

- Martimbianco ALC, Torloni MR, Andriolo BN, Porfírio GJ, Riera R. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) for patellofemoral pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Dec 12;12(12):CD011289.

- Shanks P, Curran M, Fletcher P, Thompson R. The effectiveness of therapeutic ultrasound for lower limb musculoskeletal conditions: A literature review. Foot (Edinb). 2010 Dec;20(4):133-9.

- Van der Heijden RA, Lankhorst NE, van Linschoten R, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, van Middelkoop M. Exercise for treating patellofemoral pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 20;1:CD010387.

- Logan CA, Bhashyam AR, Tisosky AJ, Haber DB, Jorgensen A, Roy A, Provencher MT. Systematic Review of the Effect of Taping Techniques on Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Sports Health. 2017 Sep/Oct;9(5):456-461.

- Lan TY, Lin WP, Jiang CC, Chiang H. The Immediate effect and predictors of taping’s effectiveness for patellofemoral pain syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2010 Aug;38(8):1626-30.

- Collins NJ, Barton CJ, van Middelkoop M, Callaghan MJ, Rathleff MS, Vicenzino BT, Davis IS, Powers CM, Macri EM, Hart HF, de Oliveira Silva D, Crossley KM. 2018 Consensus statement on exercise therapy and physical interventions (orthoses, taping and manual therapy) to treat patellofemoral pain: recommendations from the 5th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Gold Coast, Australia, 2017. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Sep;52(18):1170-1178.

- Dixit S, DiFiori JP, Burton M, Mines B. Management of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Jan 15;75(2):194-202.

- Crossley KM, Stefanik JJ, Selfe J, Collins NJ, Davis IS, Powers CM, McConnell J, Vicenzino B, Bazett-Jones DM, Esculier JF, Morrissey D, Callaghan MJ. 2016 Patellofemoral pain consensus statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester. Part 1: Terminology, definitions, clinical examination, natural history, patellofemoral osteoarthritis and patient-reported outcome measures. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Jul;50(14):839-43.

- Kannus P, Natri A, Paakkala T, Järvinen M. An outcome study of chronic patellofemoral pain syndrome. Seven-year follow-up of patients in a randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999 Mar;81(3):355-63.

About Docquity

If you need more confidence and insights to boost careers in healthcare, expanding the network to other healthcare professionals to practice peer-to-peer learning might be the answer. One way to do it is by joining a social platform for healthcare professionals, such as Docquity.

Docquity is an AI-based state-of-the-art private & secure continual learning network of verified doctors, bringing you real-time knowledge from thousands of doctors worldwide. Today, Docquity has over 400,000 doctors spread across six countries in Asia. Meet experts and trusted peers across Asia where you can safely discuss clinical cases, get up-to-date insights from webinars and research journals, and earn CME/CPD credits through certified courses from Docquity Academy. All with the ease of a mobile app available on Android & iOS platforms!