We present a case involving a young East Asian child diagnosed with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). The toddler had a two-day fever accompanied by pyuria and, five weeks prior, had recovered from COVID-19. Initially, he was treated for a urinary tract infection. By the fifth day of his fever, he displayed bilateral non-suppurative limbus-sparing conjunctivitis, inflamed and chapped lips, and reddened extremities. Diagnostic tests revealed elevated inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytopenia, and a significantly high NT-proBNP level. Although he received timely and suitable inpatient care, mild coronary anomalies persisted nine months after his discharge.

This report aims to detail the onset and course of this MIS-C case. Notably, this case is distinct due to the initial symptom of pyuria and the demographic profile, as the child’s young age and East Asian ethnicity align more with Kawasaki disease than MIS-C.

Background

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is an exceptionally rare complication observed in children following a COVID-19 infection. Its initial recognition occurred in the UK when eight children, aged between 4 and 14, exhibited hyperinflammatory syndrome with multiple organ involvement reminiscent of Kawasaki disease (KD) shock syndrome.

Among them, four had confirmed exposure to COVID-19 within their families in May 2020. After this, larger studies and cohort analyses have shed light on this condition. For instance, a study involving 186 MIS-C patients in the USA revealed a median age of 8.3 years, with 62% being male. Organ involvement encompassed gastrointestinal (92%), cardiovascular (80%), hematologic (76%), mucocutaneous (74%), and respiratory (70%) systems, with KD-like symptoms evident in 74% of cases. The majority exhibited heightened inflammatory markers.

In late 2021, an Asian country’s Ministry of Health (MOH) issued a statement highlighting four local MIS-C cases among over 8,000 pediatric COVID-19 cases recorded since the pandemic’s onset.

Fortunately, all four patients have recuperated, as the MOH statement indicated. We document a case of MIS-C in a boy under the age of two, who initially sought medical attention at a public primary care facility due to a two-day fever in December 2021. He was subsequently diagnosed with MIS-C and received appropriate treatment. Our report elaborates on his clinical trajectory and follow-up outcomes nine months post-discharge.

Case Presentation

1. Initial Presentation at Primary Care Clinic:

- A less than 2-year-old East Asian boy, previously healthy, visited a public primary care clinic due to a 2-day fever (peak temperature of 39.5°C).

- No other localizing symptoms were observed, but urine microscopy revealed pyuria (WBC 180/hpf).

- Considering the possibility of urinary tract infection (UTI), cephalexin was initiated, and a urine culture was sent for further evaluation.

- The child had recovered from a mild symptomatic COVID-19 infection approximately five weeks before this visit, confirmed by a positive PCR test.

- An early pediatric outpatient appointment for review was scheduled.

2. Second Presentation to Children’s Emergency:

- The child returned to the children’s emergency department one day later (day 3) due to persistent fever (peak temperature 39.9°C) and a single episode of vomiting following oral antibiotics.

- Despite being clinically well, he appeared fretful and was discharged with an optimized dose of cephalexin and follow-up instructions.

3. Third Presentation to Children’s Emergency:

- Two days later (day 5), the child reappeared at the children’s emergency department due to ongoing fever (peak temperature 40.5°C), irritability, and another episode of vomiting despite adhering to oral antibiotics.

- During this visit, he was febrile but hemodynamically stable with vital signs: T 39.2°C, BP 80/50 mmHg, HR 156/min, RR 35/min, SpO2 100% on room air.

- Physical examination revealed an irritable child with bilateral non-suppurative limbus-sparing conjunctivitis, red and cracked lips, and erythematous extremities.

- Consequently, he was admitted for further diagnostic investigations.

Investigations

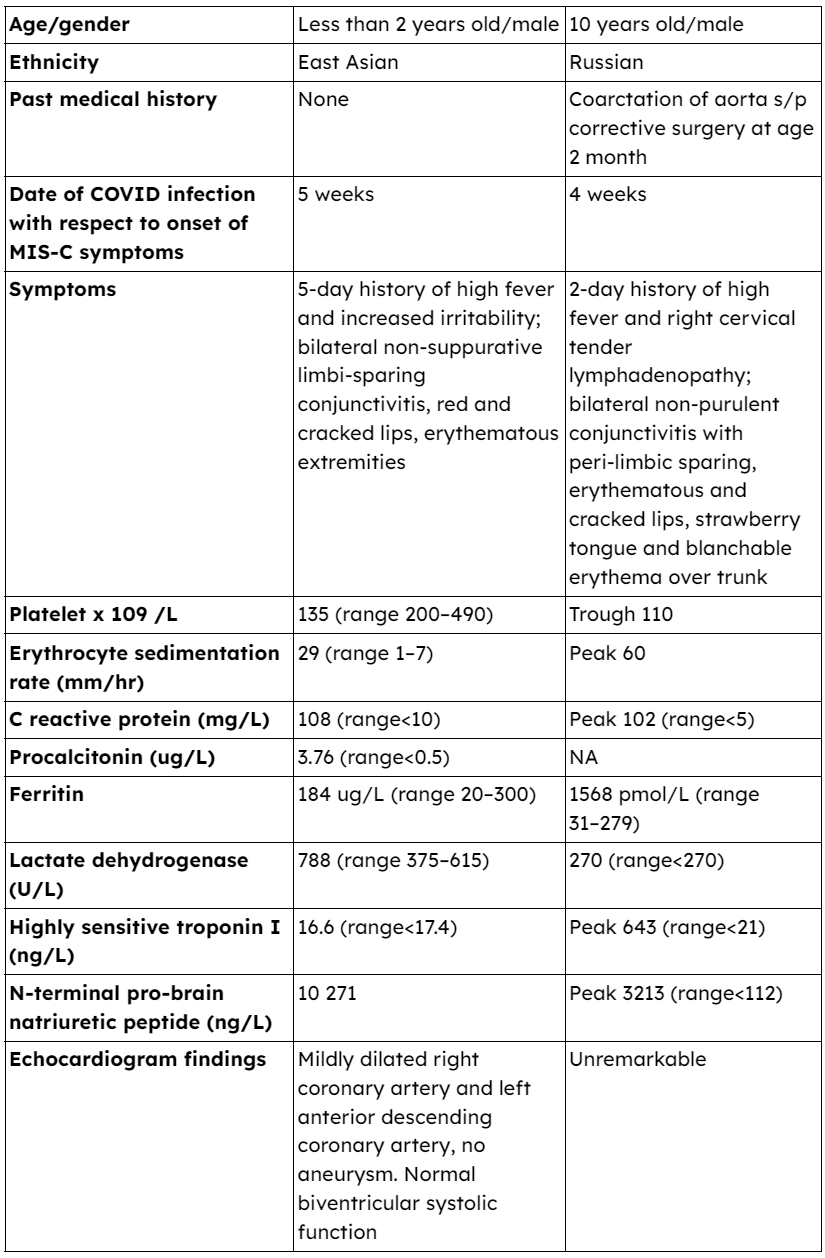

Table 1: Clinical Investigations and Findings in a Less Than 2-Year-Old East Asian Boy with MIS-C.

Differential Diagnosis

At this point, it was observed that he met all the criteria defining MIS-C, except for the timing of his Covid infection, which occurred five weeks before the onset of his current illness, as opposed to the typical 4-week interval. He exhibited persistent fever for five days, along with mucosal, hematological, and cardiac manifestations indicative of systemic inflammation. Potential differential diagnoses considered include incomplete Kawasaki disease (as he met three out of the five criteria of KD, including mucositis, non-exudative conjunctivitis, and extremity changes) and toxic shock syndrome (ruled out due to the absence of hypotension and rash).

Case Definition of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

1. Age and Presentation Criteria

- Individuals aged <21 years.

- Presentation with fever (≥38.0°C for ≥24 hours) or report of subjective fever lasting ≥24 hours.

2. Clinical Severity and Hospitalization

- Laboratory evidence of inflammation, including elevated markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), fibrinogen, procalcitonin, d-dimer, ferritin, lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH), or interleukin 6 (IL-6).

- Evidence of clinically severe illness requiring hospitalization.

3. Multisystem Organ Involvement

- Multisystem (≥2) organ involvement encompasses cardiac, renal, respiratory, hematologic, gastrointestinal, dermatologic, or neurological systems.

4. Exclusion of Alternative Diagnoses

- No alternative plausible diagnoses.

5. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Criteria

- Positive for current or recent SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by RT-PCR, serology, or antigen test.

- Exposure to a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 case within the four weeks before the onset of symptoms.

Treatment

1. Treatment Initiation:

- Commenced aspirin at 4.4 mg/kg as an antiplatelet agent.

- Administered IV Augmentin upon admission due to suspected urinary tract infection.

2. Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG):

- Received two doses of IVIG (1 g/kg) on the second and third days of admission, following the consensus treatment protocol for MIS-C.

3. Clinical Response:

- Only demonstrated partial clinical improvement.

- Features of persistent fever and Kawasaki disease (KD) recurrence were observed.

4. Follow-up TTE:

- Conducted on the fourth day of admission.

- Revealed an increased LAD dimension (LAD=2.9 mm, z-score +4.13) and mild dilatation of the mainstem left coronary artery (LCA=2.71 mm, z-score +2.08).

5. Steroid Treatment:

- Initiated IV methylprednisolone at a dosage of 10 mg/kg daily on the fifth day of admission for three days.

- A rapid and favorable response was achieved with this regimen.

6. Discharge:

- Released on the eighth day of admission.

- Prescribed a daily regimen of 50 mg aspirin and a weaning dose of prednisolone.

7. Antibiotic Adjustment:

- Augmentin was discontinued on the fourth day as Moraxella osloensis identified in the initial blood culture was likely a contaminant.

Outcome and Follow-up

Three months post-discharge, a follow-up transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed a persistently mildly dilated left anterior descending artery (LAD=2.30 mm, z-score +2.42), prompting the continuation of aspirin. Subsequent TTE at the 6-month mark indicated the restoration of normalcy in coronary arteries (LAD=2.16 mm, z-score +1.79). The NT-proBNP level significantly decreased to 186 pg/mL (from a peak of 15,153 pg/mL), and the platelet count normalized to 335,000 /mL, leading to the discontinuation of aspirin.

However, a subsequent TTE at the 9-month mark revealed a mild dilation of the left anterior descending coronary artery once again (LAD=2.30 mm, z-score +2.19). Consequently, the patient is scheduled for another TTE in six months to reassess the condition of his coronary arteries.

Discussion

The patient met all the Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) criteria, with mucocutaneous, hematological, and cardiovascular involvement manifestations and elevated inflammatory markers (CRP and ESR) observed on day 5 of illness.

Notably, persistent mild coronary artery dilation was observed at the 9-month follow-up. In contrast, another MIS-C case involved a boy under four years old who presented with a 5-day high fever and classical Kawasaki disease (KD) features (see Table 2). The patient experienced fluid-refractory cardiogenic shock, necessitating dual inotropic support and continuous positive airway pressure for myocardial dysfunction, ultimately recovering well by Day 12 of admission.

The case stands out due to the patient’s exceptionally young age (less than two years old), contrasting with the typical median age of MIS-C cases (8 years old). While meeting all MIS-C criteria, the patient only fulfilled three of the five KD criteria (mucositis, non-exudative conjunctivitis, and extremity changes). Demographically, his age and ethnicity align more with KD than MIS-C. However, the presence of vomiting on days 3 and 5 suggests gastrointestinal involvement, a common feature in MIS-C compared to KD. Comparing our case with the first reported MIS-C case in China, a 10-year-old ethnic Russian boy, our patient was younger, of East Asian ethnicity, and had no significant prior medical history. Despite hemodynamic stability, he presented with coronary abnormalities and received both IVIG and IV methylprednisolone due to persistent fever and KD symptoms.

Table 2: Comparison of clinical features and laboratory parameters of the current case study patient and the 10-year-old Russian patient

Regarding laboratory results, the child exhibited mild thrombocytopenia, with a platelet count of 135,000 /mL, and lymphopenia, indicated by an absolute lymphocyte count of 220,000 /mL, consistent with MIS-C. When comparing Kawasaki Disease (KD) with MIS-C, KD typically presents with thrombocytosis beyond the initial acute phase (first week), whereas MIS-C is characterized by ongoing thrombocytopenia. Recent insights have shed light on the underlying pathophysiology of this distinction. The contrasting mechanisms stem from their respective immunopathogenesis. In KD, the immune complex-mediated pathogenesis activates inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and monocytes, leading to platelet recruitment and subsequent thrombocytosis. In contrast, MIS-C involves the secretion of mediators to combat the COVID-19 virus, inadvertently suppressing bone marrow function and resulting in thrombocytopenia. This differential characteristic is noteworthy.

Furthermore, concerning the child’s initial presentation, the outpatient clinic initially assessed him for fever and pyuria, suspecting a pediatric urinary tract infection (UTI). Given that fever and vomiting are prevalent pediatric symptoms encountered in primary care settings, it’s crucial to recognize that these symptoms, when accompanied by pyuria in a child with a recent COVID-19 infection, may indicate MIS-C rather than, or in addition to, a UTI. Vigilant monitoring and appropriate follow-up guidance are essential to prevent overlooking an MIS-C diagnosis.

Conclusion

The case report underscores the diverse clinical presentations of MIS-C, especially in younger age groups, and the challenge of distinguishing it from KD. The prolonged coronary artery abnormalities emphasize the importance of long-term follow-up in such cases. Despite our patient’s unique demographics, the timely administration of IVIG and IV methylprednisolone contributed to a positive outcome. Ongoing monitoring and further research are crucial to understanding and managing MIS-C effectively in pediatric populations.

Reference

- Lo KA, Goh LG, Ramachandran RMultisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) of a toddler initially presenting with fever and pyuria.BMJ Case Reports CP 2024;17:e253756.

- Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, et al. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020;395:1607–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094.

- Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 2020;383:334–46. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021680.

- MOH media statement on Paediatric MIS-C cases in Singapore. 2021. Available: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/media-statement-on-paediatric-mis-c-cases-in-singapore

- Centers for disease control and prevention. 2020. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/mis/mis-c/hcp/index.html

- Leow OMY, Aoyama R, Chan SM. The evolution of severity of paediatric COVID-19 in Singapore: verticaltransmission and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Ann Acad Med Singap 2022;51:115–8. doi:10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.2021426.

- Chua GT, Wong JSC, Chung J, et al. Pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2: a case report. Hong Kong Med J 2022;28:76–8. doi:10.12809/hkmj219689.

About Docquity

If you need more confidence and insights to boost careers in healthcare, expanding the network to other healthcare professionals to practice peer-to-peer learning might be the answer. One way to do it is by joining a social platform for healthcare professionals, such as Docquity.

Docquity is an AI-based state-of-the-art private & secure continual learning network of verified doctors, bringing you real-time knowledge from thousands of doctors worldwide. Today, Docquity has over 400,000 doctors spread across six countries in Asia. Meet experts and trusted peers across Asia where you can safely discuss clinical cases, get up-to-date insights from webinars and research journals, and earn CME/CPD credits through certified courses from Docquity Academy. All with the ease of a mobile app available on Android & iOS platforms!