Malaria, commonly known as the “rainy season disease,” is caused by Plasmodium species, whereas leptospirosis, a zoonotic infection, is triggered by the spirochete Leptospira interrogans. Though rare, coinfection with both diseases is possible. Before considering vector-borne fever, it’s crucial to rule out other potential causes, even if the patient is at high risk. This case report highlights an extraordinary coinfection and its unique presentation, emphasising the importance of early detection and prompt treatment to avoid fatal outcomes. Coinfections of Falciparum Malaria with diseases like dengue, hantavirus, and filariasis have been documented, and more recently, instances of malaria-leptospirosis coinfections have surfaced, especially in tropical regions.

In this report, we explore a complex case of a young male suffering from a coinfection of meningoencephalitis, leptospirosis, and severe malaria, which required ICU care. Distinguishing between single infections and coinfections can be challenging due to the diverse presentations, potentially complicating clinical features. If a coinfection is overlooked, the patient’s condition may deteriorate rapidly without appropriate treatment. This case showcases the unusual combination of these infections and delves into the management strategies and clinical progression of such life-threatening scenarios. Meningoencephalitis, a condition mimicking both meningitis and encephalitis, adds another layer of complexity to the case.

Introduction to Falciparum Malaria, Leptospirosis, and Vibrio mimicus Encephalitis

Leptospirosis and other infectious diseases, such as malaria, often share similar geographic distributions. Coinfections with diseases like malaria are not uncommon [1]. However, there have been only a few reported cases of coinfection with leptospirosis and malaria. The clinical features of these infections are so similar that distinguishing between single and dual infections can be challenging. When patients with multiple infections present with significant clinical symptoms, improper management can lead to worse outcomes. Coinfections frequently result in misdiagnosis, complicating the situation and potentially aiding the pathogens. Environmental exposure and the presence of similar pathogenic microorganisms in the environment may increase the likelihood of coinfections, leading to delayed or insufficient diagnosis [2].

Leptospirosis outbreaks are common in tropical and subtropical regions and are often triggered by natural disasters such as severe flooding and prolonged periods of rainfall. One of the well-known risk factors for leptospirosis is direct contact with water, soil, or vegetation contaminated with pathogenic leptospires during water-related events. Certain occupations, such as agriculture, mining, sewage maintenance, and participating in military exercises, also increase the risk of infection. Leptospirosis can range from a mild, self-limiting febrile illness to a life-threatening condition involving multi-organ dysfunction. In severe cases, complications may include cerebral infections such as aseptic meningitis, meningoencephalitis, or cortical subarachnoid haemorrhage, which can manifest as agitation, psychosis, impaired consciousness, or coma.

India faces significant morbidity and mortality due to malaria, a deadly parasitic disease. Early detection and comprehensive treatment are crucial for controlling the condition. The Indian government’s national vector-borne disease control program reports approximately 1.5 million confirmed cases annually, nearly half attributed to Plasmodium falciparum. Prompt treatment is essential for curing malaria, as delays in medical care can have fatal outcomes. Rapid and effective treatment is also vital for preventing the spread of the disease. Malaria should be considered in patients who have recently travelled to endemic areas. The incubation period for Plasmodium vivax is 12-14 days, while for Plasmodium falciparum it is 12-17 days [3,4]. Neurological complications of malaria can include seizures, psychosis, agitation, impaired consciousness, and even coma.

Vibrio species are a group of aquatic bacteria commonly found in brackish or marine environments. The three main Vibrio species responsible for most human infections are Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio vulnificus, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Although Vibrio mimicus and Vibrio cholerae are genetically and phenotypically distinct, V. cholerae can cause diarrheal disease by secreting cholera toxin. Vibrio mimicus is associated with seafood, marine samples, human diarrheal stools, acute otitis from seawater exposure, and nested eggs. However, recent medical literature has not reported any cases of bacterial meningitis caused by Vibrio mimicus. Generally, Vibrio species are not known to cause meningitis at any age. If such an infection occurs, it is believed that these pathogens may invade the central nervous system through bloodstream infection in an immunocompromised state [5]. Further research is needed on the neurological manifestations of Vibrio mimicus. In this report, we describe a rare case of a young person who was successfully treated with intravenous antibiotics, steroids, antimalarials, and other supportive medications for bacterial meningoencephalitis caused by Vibrio mimicus, Plasmodium falciparum malaria, and leptospirosis. This case represents the first reported instance of meningoencephalitis attributed to Vibrio mimicus in an otherwise healthy male.

Case Presentation

Patient Profile:

- A 24-year-old male from northeastern Maharashtra

- Previously in good health

- No history of tuberculosis, diabetes mellitus, or hypertension

- No history of alcohol consumption or smoking

Presenting Complaints:

- High-grade fever

- Severe headache

- Dark-coloured urine

- Myalgia

- Altered mental status

Examination Findings:

- Neck stiffness and signs of meningeal irritation

- Progressive worsening of sensorium over the past day:

- Diminished responsiveness to commands

- Decreased verbal output

- Inability to move limbs

- No history of abnormal posture, eye-rolling, mouth-frothing, chest pain, palpitations, nausea, cold, or cough

- Feverish and in poor general condition

- Vital signs:

- Blood pressure: 80/60 mmHg

- Pulse rate: 120 beats per minute

- Oxygen saturation (room air): 90%

- Central nervous system examination:

- Neck stiffness

- Positive Brudzinski and Kernig signs

- Pupils reactive to light at 4 mm

- Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score: E2V1M4

- Bilateral basal crepitations on auscultation

- Drowsiness

Progression:

- Worsening condition on the following day:

- Increased drowsiness

- GCS score: E1V1M3

- Required intubation

Laboratory Test Results:

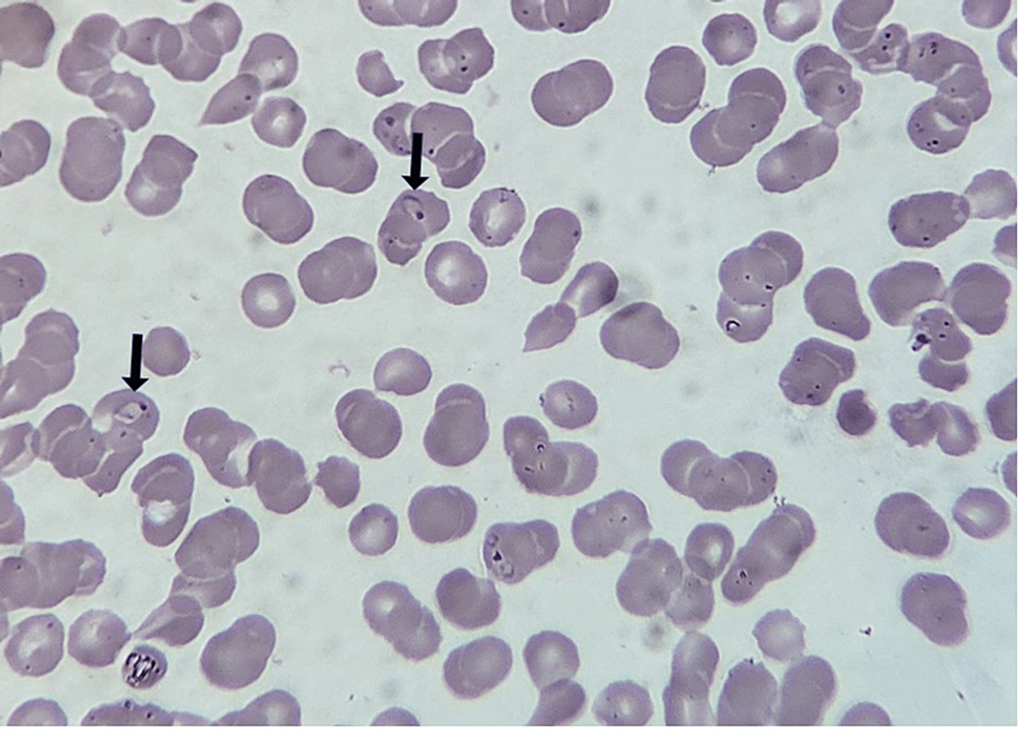

- Severe anaemia

- Thrombocytopenia

- Elevated liver enzymes (Table 1)

Diagnostic Findings:

- Syndromic examination led to the discovery of falciparum parasitaemia.

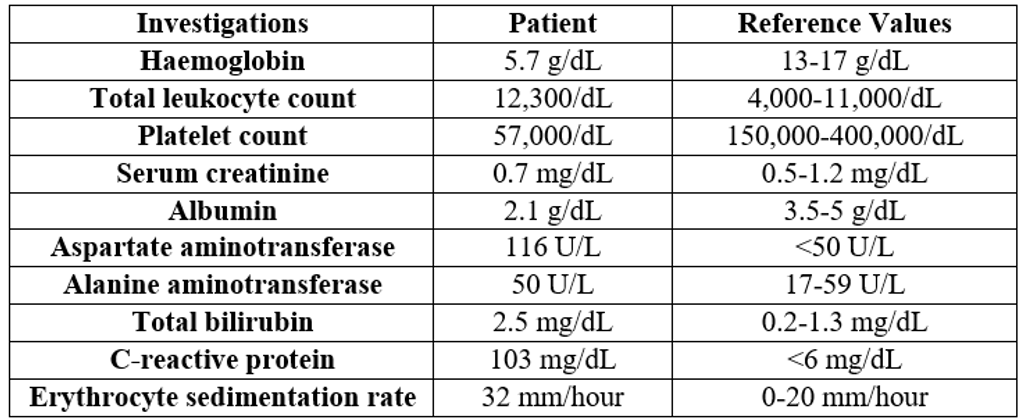

- Thick blood smear revealed falciparum ring formations (Figure 1).

- Blood, sputum, and urine cultures were negative.

- HIV and hepatitis tests were negative.

Occupational and Environmental History:

- The patient worked in a paddy field where rodents were occasionally seen.

- Leptospirosis was suspected based on occupational exposure.

Further Investigations:

- Leptospira microscopic agglutination test (MAT) was performed, confirming the diagnosis.

- Brain MRI indicated possible acute meningoencephalitis (Figure 2).

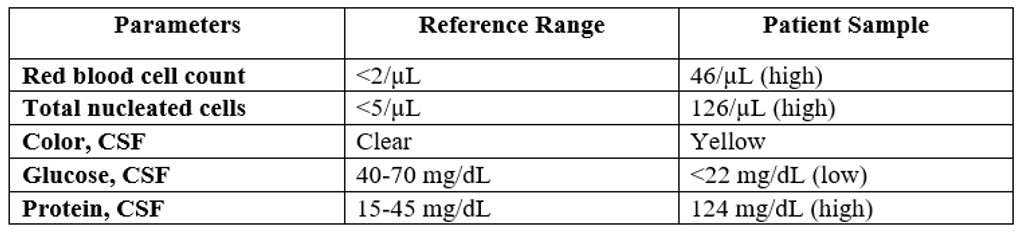

- Lumbar puncture (LP) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tests confirmed bacterial meningitis (Table 2).

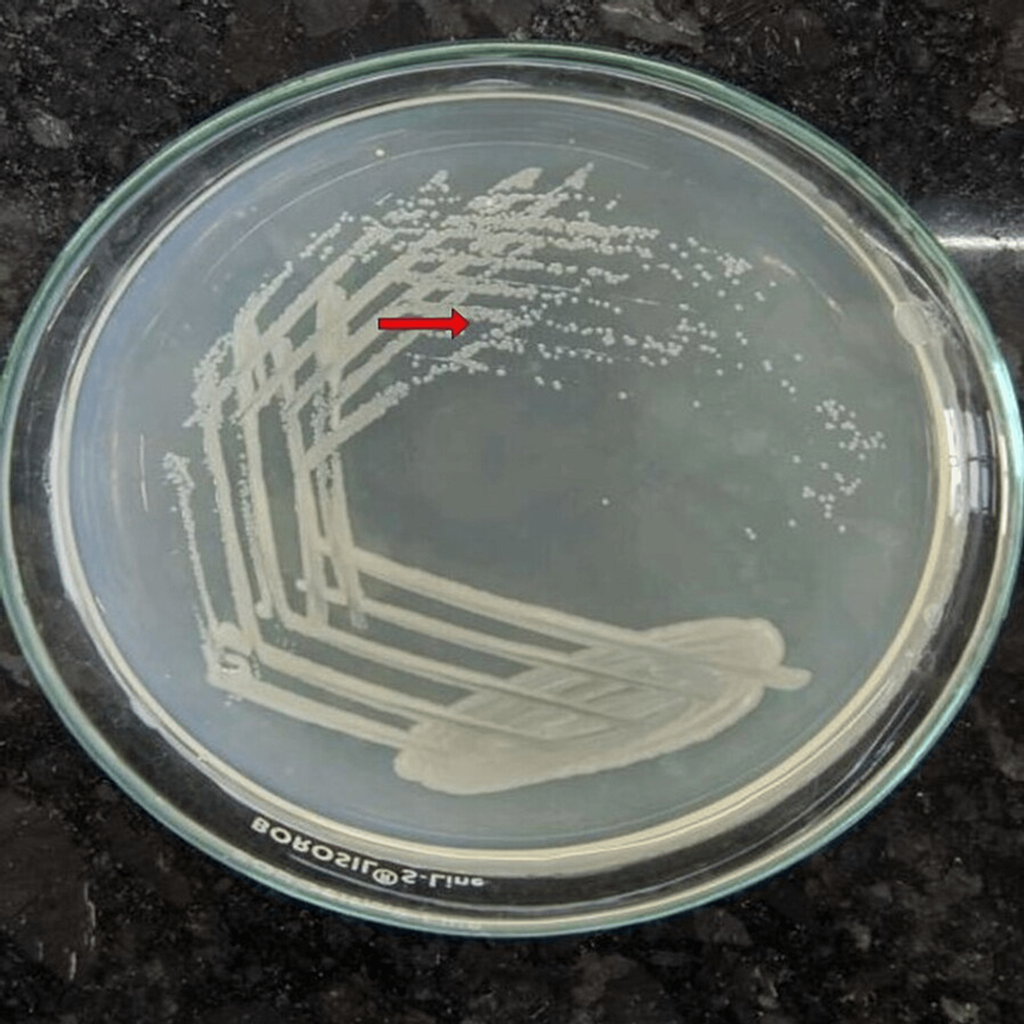

- Vibrio mimicus was eventually cultured from CSF samples (Figure 3).

Table 1: Investigation profile of the patient at the time of admission.

Figure 1: Plasmodium rings on a thick blood smear (black arrows).

Figure 2: Patient’s magnetic resonance imaging scan revealing the presence of encephalitis (white arrow).

Table 2: Cerebrospinal fluid analysis on presentation.

Figure 3: Growth of Vibrio mimicus in cerebrospinal fluid on nutrient agar medium (red arrow).

Initial Treatment:

- Empirical therapy with artesunate injections:

- 120 mg at 0, 12, and 24 hours

- 120 mg once daily for seven days

- Supportive treatments included:

- Penicillin 1.5 MU IV every six hours

- Ceftriaxone 2 g twice daily

- Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for seven days

- Primaquine tablets 15 mg twice daily

Progress Over Three Days:

- Gradual reduction in haemolysis

- Improvement in sensorium

- Patient became afebrile

Considerations:

- Infections in tropical regions are common and may go undiagnosed.

- Untreated coinfections can lead to adverse outcomes.

Discharge and Follow-Up:

- After seven days of intravenous antiparasitic treatment, the patient was discharged.

- Advised to check on family members after discharge.

- A follow-up visits after one month showed good progress.

Discussion

Malaria hits hard worldwide, with an estimated 500 million cases annually, including 2-3 million severe cases and 1.1 million deaths. In tropical heat, leptospirosis also thrives, often flaring up in massive epidemics after heavy rains. This disease is endemic in various regions, including China, Southeast Asia, Africa, South and Central America, India’s Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and the Andaman Islands. Coinfections are common, as leptospirosis and malaria frequently overlap in these tropical locales. A recent study by Singhsilarak et al. revealed that 7.7% of adults with falciparum malaria also had leptospirosis [6]. Yet only 15 clinical cases of this dual infection (eight from India and seven from Thailand) have been documented. These cases often go under the radar because leptospirosis frequently presents as mild or self-limiting, shares symptoms with other febrile illnesses, and lacks readily available diagnostic tests. When it does appear, leptospirosis can cause severe haemorrhagic pulmonary lesions with an incidence ranging from 20% to 70%, sometimes proving fatal, and the severity is not always linked to the presence of jaundice [2].

Severe falciparum malaria can lead to dangerous organ sequestration, causing endothelial dysfunction that may spark micro-thrombosis and vasospasm. This dysfunction can diminish blood flow to vital organs and elevate lactic acidosis. When faced with a patient showing fever, renal failure, and jaundice, consider severe leptospirosis, severe malaria, enteric fever, hantavirus, fulminant viral hepatitis, or scrub typhus in the differential diagnosis. Given the local epidemiology and the presence of haemolysis and lung injury, the focus narrows to viral hepatitis (especially hepatitis E), leptospirosis, typhoid, and haemolysis. For managing coinfections, starting treatment with third-generation cephalosporins, doxycycline, and antimalarials is essential, as they target a range of pathogens, including malaria parasites, leptospirosis, rickettsia, and salmonella. Delayed recognition of acute leptospirosis can lead to unnecessary deaths, emphasising the need for timely and precise antibiotic use guided by clinical expertise, which is irreplaceable by adjunct therapies [7].

Vibrio species, commonly found in brackish or marine waters, include Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio vulnificus, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus—the three main culprits behind human infections. These bacteria can cause two primary types of illnesses: cholera and non-cholera infections. Vibrio cholerae is notorious for causing cholera, a severe form of diarrhoea. Non-cholera Vibrio species, such as Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus, are responsible for a range of illnesses with symptoms varying by pathogen, infection route, and host factors. Since its identification in 1983, Vibrio mimicus has emerged as a rare cause of gastroenteritis linked to recent seafood consumption and acute otitis media from seawater exposure. While these bacteria are more commonly found in marine environments, Vibrio mimicus and others can also thrive in freshwater [8].

To our knowledge, this is the first documented case of meningitis caused by Vibrio mimicus. The patient, a student working in the mud due to his father’s farming occupation, likely contracted the infection from soil exposure. This contact may have led to both bacteraemia and subsequent meningitis. Early detection of meningoencephalitis is crucial for effective and targeted treatment, yet it still results in significant morbidity and mortality. Typically, encephalitis may start unilaterally but can later spread to both sides, unevenly affecting the temporal and contralateral lobes.

Conclusions

Even though coinfections are rare, it’s crucial to stay vigilant. A delayed diagnosis can lead to increased morbidity and mortality. Consider starting empirical treatment with third-generation cephalosporins, doxycycline, and antimalarials for patients with severe malaria presenting with fever, thrombocytopenia, and altered liver and kidney function tests. This approach covers the main culprits, including malarial parasites, leptospira, rickettsia, and salmonella. Since severe leptospirosis can deteriorate quickly, prompt and careful treatment is essential.

References

- Saboo K, Gemnani R, Kumar S, et al. (August 21, 2023) Falciparum Malaria, Leptospirosis, and Vibrio mimicus Encephalitis in a Resilient Patient: A Remarkable Case of Triple Infection Survival. Cureus 15(8): e43879. doi:10.7759/cureus.43879.

- Issaranggoon na ayuthaya S, Wangjirapan A, Oberdorfer P: An 11-year-old boy with Plasmodium falciparum malaria and dengue co-infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2014, 2014:10.1136/bcr-2013-202998.

- Srinivas R, Agarwal R, Gupta D: Severe sepsis due to severe falciparum malaria and leptospirosis co-infection treated with activated protein C. Malar J. 2007, 6:42. 10.1186/1475-2875-6-42.

- Kota V, Kabra R, Kumar S, Acharya S, Gemnani RR: Plasmodium falciparum, vivax and scrub typhus in a young adult male: surviving a triple strike. Cureus. 2022, 14: e30176. 10.7759/cureus.30176.

- Kumar S, Diwan SK, Mahajan SN, Bawankule S, Mahure C: Case report of Plasmodium falciparum malaria presenting as wide complex tachycardia. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2011, 1: S305-6. 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60178-0.

- Patel M, Kumar S, Acharya S, Mudey G, Bhagawati J, Patel S, Ahuja A: Serratia fonticola causing acute meningoencephalitis in a young male: a first case report. Med Sci. 2023, 27: e15ms2666. 10.54905/disssi/v27i131/e15ms2666.

- Singhsilarak T, Phongtananant S, Jenjittikul M, et al.: Possible acute coinfections in Thai malaria patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006, 37:1-4.

- Cardoso J, Gaspar A, Esteves C: Severe leptospirosis: a case report. Cureus. 2022, 14: e30712. 10.7759/cureus.30712.

- Skandalos I, Christou K, Psilas A, Moskophidis M, Karamoschos K: Mycotic abdominal aortic aneurysm infected by Vibrio mimicus: report of a case. Surg Today. 2009, 39:141-3. 10.1007/s00595-008-3808-5.

About Docquity

If you need more confidence and insights to boost careers in healthcare, expanding the network to other healthcare professionals to practice peer-to-peer learning might be the answer. One way to do it is by joining a social platform for healthcare professionals, such as Docquity.

Docquity is an AI-based state-of-the-art private & secure continual learning network of verified doctors, bringing you real-time knowledge from thousands of doctors worldwide. Today, Docquity has over 400,000 doctors spread across six countries in Asia.

Meet experts and trusted peers across Asia where you can safely discuss clinical cases, get up-to-date insights from webinars and research journals, and earn CME/CPD credits through certified courses from Docquity Academy. All with the ease of a mobile app available on Android & iOS platforms!