Diffuse oesophageal leiomyomatosis, a rare benign condition in children, is spotlighted in this case involving a young girl with a 2-year history of recurrent respiratory infections. A chest X-ray revealed a retrocardiac lesion, later identified as an oesophageal mass through CT imaging. The patient underwent major surgery, including an Ivor-Lewis eosophagogastrectomy and Heineke-Mikulicz pyloroplasty. Pathology confirmed type I diffuse oesophageal leiomyomatosis, and postoperative haematuria led to a diagnosis of Alport syndrome.

This case underscores the importance of considering oesophageal leiomyomatosis in patients with dysphagia or respiratory symptoms, especially when linked to Alport syndrome. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy is crucial for diagnosis, and surgical resection remains the definitive cure.

Introduction of Diffuse oesophageal leiomyomatosis (DEL)

Diffuse oesophageal leiomyomatosis (DEL) is an exceptionally rare condition in children, with few established guidelines. In 1975, Fernandes divided DEL into two types:

(1) widespread thickening of the oesophageal muscles and

(2) large, fused myomatous nodules (2,3). Early reports also mentioned diffuse fibromyoma, oesophageal hypertrophic stenosis, and leiomyoma like Fernandes type 2 lesions, often identified through autopsy (4,5).

By 1983, Torres and Guarner linked DEL to Alport syndrome (DEL-AS), while other research indicated that this leiomyomatosis could affect various organs, including the tracheobronchial tree, genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts, and anorectal muscles (9,13). Imaging studies frequently reveal significant thickening in the distal oesophagus, sometimes extending to the esophagogastric junction, causing stenosis longer than in achalasia (5,4,15). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided biopsy is crucial for diagnosing these muscle lesions (17). Treatment options have evolved from periodic oesophageal dilations and myotomy/myectomy to more comprehensive approaches like oesophageal resection and replacement surgeries (2,5).

Case Presentation

Patient Profile

- Early middle childhood girl with recurrent respiratory infections.

Medical History

- Respiratory Episodes: Four previous episodes of bronchitis and pneumonia over the past two years.

- Current Presentation: Hospitalized with a fifth episode of bronchitis.

Diagnostic Findings

- Chest X-ray (CXR): Incidental finding of a retrocardiac mass (Figure 1A).

- CT Imaging: Revealed long-segment oesophageal thickening (Figure 1B).

Additional History

- Feeding Issues: History of progressively poor feeding.

- Previous Admissions: Haematuria was noted to begin in early childhood without further investigation.

Physical and Laboratory Measurements

- Body Weight: 15.35 kg.

- Body Mass Index (BMI): 12.77.

- Serum Blood Levels:

- Blood Urea Nitrogen: 15 mg/dL.

- Creatinine: 0.38 mg/dL.

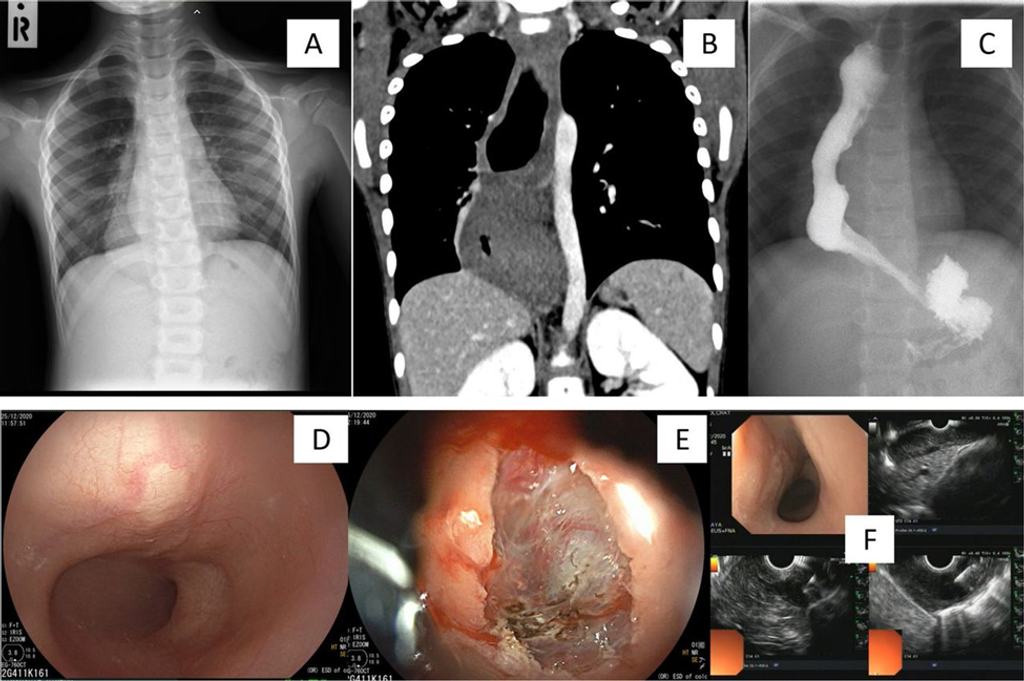

Figure 1

(A): Chest X-ray taken at the fourth episode of bronchitis incidentally detected a retrocardiac mass lesion prominent in right-side hemithorax. (B): CT imaging confirmed oesophageal origin extending to the gastro-oesophageal junction. (C): Oesophagogram demonstrated a longer oesophagogastric junction length than that seen typically with achalasia. (D): Oesophagoscopy revealed a yellowish submucosal mass. (E): Submucosal single-incision knife biopsy revealed the histopathological reporting of normal muscular features (endoscopy photos, courtesy of Associate Professor Chonlada Krutsri, MD, FRCST). (F): Subsequent endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with biopsy reported the same findings, which were interpreted as a muscular mass lesion with confidence in visualisation of the accurate biopsy site (EUS photos, courtesy of Assistant Professor Taya Kitiyakara, MD, MBBS).

Diagnostic Procedures

- Oesophagography: Imaging performed (Figure 1C).

- Oesophagogastroscopy: Conducted with a submucosal single-incision knife biopsy.

- EUS-Guided Biopsy: Performed to assess further the oesophageal mass (Figures 1D–F).

Biopsy Results

- Pathological Findings: Biopsy specimens were inconclusive, and it was difficult to differentiate clearly between normal and hypertrophic smooth muscle.

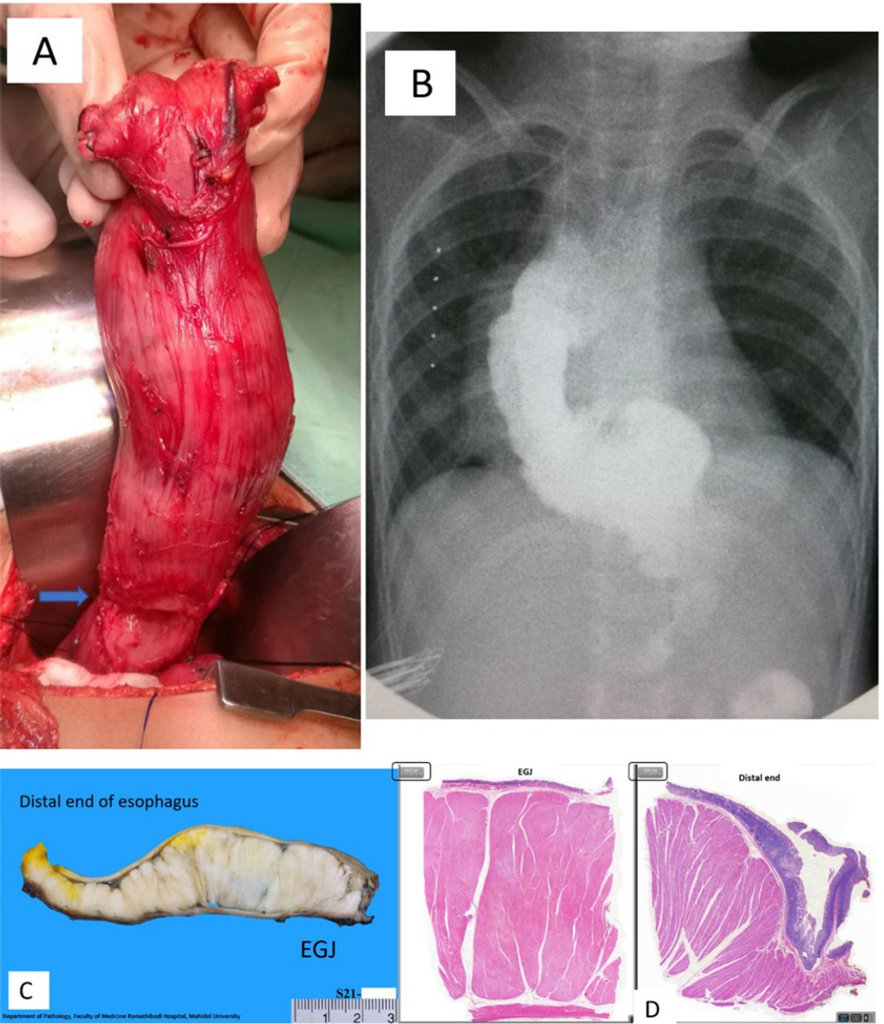

Surgical Intervention

- Surgery: Ivor-Lewis oesophagogastrectomy with gastric pull-up performed (Figure 2A).

- Additional Procedure: Heineke-Mikulicz pyloroplasty was conducted.

Postoperative Follow-up

- Routine Contrast Study: Follow-up imaging performed post-surgery (Figure 2B).

Final Diagnosis

- Surgical Specimen Findings: Confirmed Fernandes type 1 leiomyomatosis (Figures 2C, D).

Figure 2

(A): Right thoracotomy view—the stomach and oesophagus were mobilised, and the diffuse thickening of the oesophagus was seen with transverse grooves on the proximal segment (blue arrow); esophagogastric junction was at the surgeon’s grip area. The line of surgical resection was demarcated by the limits of the palpable mass and the azygos vein. (B): Eighth postoperative day—the replacement graft—normal contrast study showing ‘no leak’ and graft substitute reflux. (C): Gross pathology—a 12 cm long and 4 cm maximal circumference lesion showing diffuse muscular wall thickening measuring 0.8–2.5 cm with prominent thickening of the inner circular muscle wall in longitudinal cut sections. (D): Histopathological staining (H&E stain—2000-micron sections; black rectangle—notable findings seen are the prominent circular muscle layers with relative thinning of the longitudinal layer and muscularis mucosae. The section of EGJ junction and the distal end of the oesophagus had pathology findings compatible with diffuse oesophageal leiomyomatosis (Gross and histopathology photos, courtesy of Pathology Department – Bantita Phruttinarakorn, MD).

Postoperative Complications

- Haematuria: Developed on the third postoperative day, prompting clinical suspicion of Alport syndrome.

Clinical Examinations

- Orbital and Auditory Exams: Both confirmed to be normal.

Parental Decision

- Genetic Testing: Parents declined full medical genetics testing.

Diagnostic Findings

- Renal Biopsy: Conducted with histopathology and electron microscopy.

- Microscopy Results: Thin focal thickness membranes, areas of duplication, and diffuse foot process effacement of podocytes are hallmark features of Alport syndrome.

Family Screening

- First- and Second-Degree Relatives: Normal chest X-ray films and urinalysis results.

- Family Pedigree: No other family members in the three generations showed typical features of Alport syndrome.

Postoperative Outcome

- 2 Months Postoperatively: Patient had trouble eating and swallowing.

- Oesophagogram Study: Showed narrowed anastomosis and gastro-oesophageal reflux.

- Stricture Management: Mild stricture was successfully treated with balloon dilation.

1-Year Follow-up

- CT Scan Findings: Non-progressive thickening of the residual oesophagus was observed.

2-Year Follow-up

- Weight Gain: The patient gained 2 kg.

- Recurrent Stricture: Occurred due to reflux inflammation of the substitution graft anastomosis despite full doses of proton-pump inhibitors.

- Interventions: Four oesophageal balloon dilations were performed due to periodic dysphagia.

- Endoscopic Stricturotomy: Carried out, restoring normal eating for over one year.

Discussion

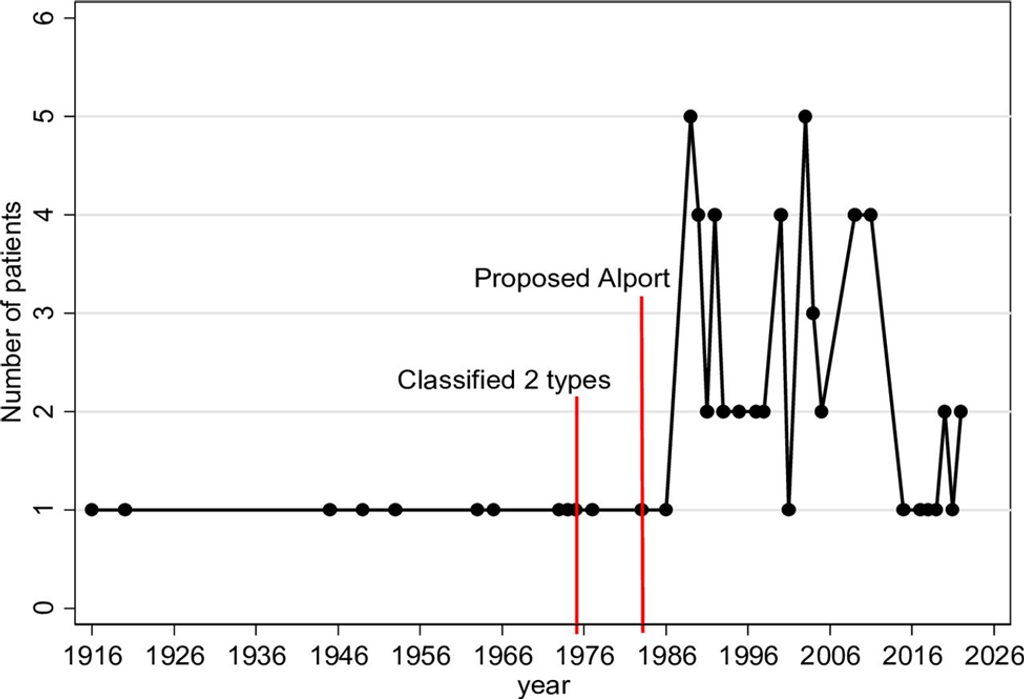

The narrative review examined literature published from 1916 to December 2022, focusing on paediatric patients with symptoms before the age of 18. They used search terms like “esophag*,” “leiomyomatosis,” “muscular hypertrophy,” and “human” on PubMed and Google. The team identified 67 previously reported cases, and our study presents the 68th case.

Statistical Analysis:

The research team used Stata 14.1 software for the statistical analysis:

- Categorical Data: Analysed using Fisher’s exact and chi-square (χ²) tests.

- Continuous Data: Analysed using the Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney test and Student’s t-test.

- Nominal Variables: Compared using Cramér’s V correlation.

Figure 3: Number of patients reported in each year from the first available report in 1916 highlighted along with the year defining the disease classification (1975) and the year of the first proposed linked associations with Alport syndrome (1983) (Created by Suraida Aeesoa, MSc).

Figure 3: Number of patients reported in each year from the first available report in 1916 highlighted along with the year defining the disease classification (1975) and the year of the first proposed linked associations with Alport syndrome (1983) (Created by Suraida Aeesoa, MSc).

Historical Context:

The first confirmed diagnosis of esophageal leiomyomatosis was made in 1975. In 1983, links between esophageal leiomyomatosis (DEL) and Alport syndrome (DEL-AS) were identified. Before these diagnoses, patients were frequently misdiagnosed with esophageal achalasia. Esophageal leiomyomatosis was often discovered during detailed postmortem examinations. Many cases also involved incidental findings of esophageal mass lesions.

Symptoms and Demographics:

The primary symptoms are related to difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) and gastroesophageal reflux disease. For cases diagnosed after 1975, the average age at onset of dysphagia was around 7.4 years (± 3.9 years). Though not widely reported, esophageal leiomyomatosis appears more common in females (2:1 ratio), whereas DEL-AS tends to occur more in males.

Associated Leiomyomas:

Leiomyomas (smooth muscle tumors) can also develop in other parts of the body, including the anorectal region, genital tract, urogenital system, tracheobronchial tree, and various parts of the intestines. These secondary tumors are often discovered around or after the primary diagnosis of esophageal leiomyomatosis, usually in adulthood. There is no significant correlation between a family history of esophageal leiomyomatosis or Alport syndrome and the occurrence of leiomyomas in other organs.

Pathological Sites and Management:

The esophagus is the most affected organ (93%), with involvement occurring in specific regions:

- Isolated distal esophagus (41%)

- Mid-to-distal esophagus (13%)

- Entire esophagus (32%)

- Esophagogastric junction (56%)

Surgical management includes partial esophageal resection or total esophagectomy. Conservative treatments, such as esophageal myotomy or myectomy, have been considered but with limited success. Follow-up care varies, with median follow-up times in studies being approximately 2.4 years (ranging from 0.3 to 21 years). There have been no reports of cancerous changes in the residual esophagus.

Diagnostic Tools:

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is valuable for diagnosing esophageal mass lesions by defining their primary location and facilitating targeted biopsies. Lesions usually affect the middle esophagus to the esophagogastric junction. A proximal esophageal location may be detected using manometry, and contrast swallow imaging can reveal issues with esophageal movement, including a thickened proximal esophagus.

Understanding the symptoms, diagnostic approaches, and management strategies is crucial for accurately diagnosing and treating esophageal leiomyomatosis in pediatric patients.

Conclusions

It is highly recommended that all paediatric patients diagnosed with an oesophageal mass undergo screening for Alport syndrome, regardless of family history. EUS-guided biopsy plays a crucial role in diagnosing suspected lesions, while surgical resection remains essential for achieving a cure. Additionally, a vigilant follow-up care program is advised to monitor and detect the emergence of new leiomyomas in other organ systems, particularly in patients with a familial history of Alport syndrome.

References

- Thanachatchairattana P,Losty P. BMJ Case Rep 2024;17: e260442.doi:10.1136/bcr-2024-260442.

- Fernandes JP, Mascarenhas MJ, Costa CD, et al. Diffuse leiomyomatosis of the esophagus: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dig Dis 1975; 20:684–90. doi:10.1007/BF01071177.

- Legius E, Proesmans W, Van Damme B, et al. Muscular hypertrophy of the oesophagus and ‘alport-like’ glomerular lesions in a boy. Eur J Pediatr 1990; 149:623–7. doi:10.1007/BF02034748.

- Blank E, Michael TD. Muscular hypertrophy of the esophagus: report of a case with involvement of the entire esophagus. Pediatrics 1963; 32:595–8:14069101.

- Hall AJ. A case of diffuse fibromyoma of the oesophagus, causing dysphagia and death. QJ Med 1916; os-9:409–28. doi:10.1093/qjmed/os-9.36.409.

- Federici S, Ceccarelli PL, Bernardi F, et al. Esophageal leiomyomatosis in children: report of a case and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg 1998; 8:358–63. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1071233.

- Ashby HT. Oesophageal obstruction in young children. Proc R Soc Med 1920; 13:146–8. doi:10.1177/003591572001301940.

- Johnston JB, Clagett OT, McDonald JR. Smooth-muscle tumours of the oesophagus. Thorax 1953; 8:251–65. doi: 10.1136/thx.8.4.251.

- Lee LS, Nance M, Kaiser LR, et al. Familial massive leiomyoma with esophageal leiomyomatosis: an unusual presentation in a father and his 2 daughters. J Pediatr Surg 2005;40: e29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.02.016.

- Guthrie KJ. Idiopathic muscular hypertrophy of oesophagus, pylorus, duodenum and jejunum in a young girl. Arch Dis Child 1945; 20:176–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.20.104.176.

- García Torres R, Guarner V. Leiomyomatosis of the esophagus, tracheo-bronchi and genitals associated with alport type hereditary nephropathy: a new syndrome. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 1983; 48:163–70.

- Pujol J, Parés D, Mora L, et al. Diagnosis and management of diffuse leiomyomatosis of the oesophagus. Dis Esoph 2000; 13:169–71. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2050.2000.00107.

- Azzie G, Bensoussan A, Spitz L. The association of anorectal leiomyomatosis and diffuse oesophageal leiomyomatosis. Pediatr Surg Int 2003; 19:424–6. doi:10.1007/s00383-003-0955-z

- Bacha D, Ferjaoui W, Zran M, et al. Pulmonary benign metastasizing leiomyoma in patient with esophageal and anorectal leiomyomatosis. Ro Med J 2022; 69:30–4. doi:10.37897/RMJ.2022.1.6.

- Levine MS, Buck JL, Pantongrag-Brown L, et al. Esophageal leiomyomatosis. Radiology 1996; 199:533–6. doi:10.1148/radiology.199.2.8668807.

- Rapp JB, Ciullo S, Mallon MG. Diffuse esophageal leiomyomatosis: a case report with surgical correlation. Clin Imaging 2019; 58:161–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2019.07.008.

- Harada A, Maehata Y, Esaki M. Diffuse esophageal leiomyomatosis diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasonography and endoscopic mucosal cutting biopsy. Dig Endosc 2017; 29:395–6. doi:10.1111/den.12852

- Denne C, Hahn H, Steinborn M, et al. Ultrasound: a helpful diagnostic tool in esophageal leiomyomatosis with alport syndrome. Ultraschall Med 2011; 32:311–2. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1245532.

- Ziogas IA, Mylonas KS, Tsoulfas G, et al. Diffuse esophageal leiomyomatosis in pediatric patients: a systematic review and quality of evidence assessment. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2019; 29:487–94. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1676507.

- Mittal RK, Kassab G, Puckett JL, et al. Hypertrophy of the muscularis propria of the lower esophageal sphincter and the body of the esophagus in patients with primary motility disorders of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98:1705–12. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003. 07587.x

- Takahashi K, Ishii Y, Hayashi K, et al. Loss of peristalsis of the esophagus due to diffuse esophageal leiomyomatosis. Endoscopy 2017;49: E95–6. doi:10.1055/s-0043-100691.

About Docquity

If you need more confidence and insights to boost careers in healthcare, expanding the network to other healthcare professionals to practice peer-to-peer learning might be the answer. One way to do it is by joining a social platform for healthcare professionals, such as Docquity.

Docquity is an AI-based state-of-the-art private & secure continual learning network of verified doctors, bringing you real-time knowledge from thousands of doctors worldwide. Today, Docquity has over 400,000 doctors spread across six countries in Asia.

Meet experts and trusted peers across Asia where you can safely discuss clinical cases, get up-to-date insights from webinars and research journals, and earn CME/CPD credits through certified courses from Docquity Academy. All with the ease of a mobile app available on Android & iOS platforms!