Restless leg syndrome (RLS) is a chronic condition marked by an irresistible urge to move the legs, often accompanied by subjective discomfort and a distinct nocturnal pattern. One overlooked cause is drug-induced RLS, which can be challenging for clinicians to identify due to its infrequency. Among the medications implicated in inducing or worsening RLS, metoclopramide stands out, with documented cases primarily associated with its intravenous use. Here, we present a case of a 33-year-old male who developed gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms following the initiation of semaglutide for weight loss. After discontinuing semaglutide, oral metoclopramide was prescribed to manage the GI symptoms.

Shortly after, the patient experienced RLS-like symptoms, which resolved within 48 hours of stopping metoclopramide. The patient had a family history of chronic RLS, and laboratory tests returned normal results. This case underscores a potential connection between metoclopramide use and transient RLS symptoms, highlighting the importance of vigilant monitoring for RLS in patients receiving this medication. Furthermore, it underscores the variability of side effects depending on the route of drug administration. Ultimately, this case serves as a reminder of the unpredictable nature of drug reactions and the critical need for careful surveillance in pharmacotherapy.

Introduction: Restless leg syndrome (RLS)

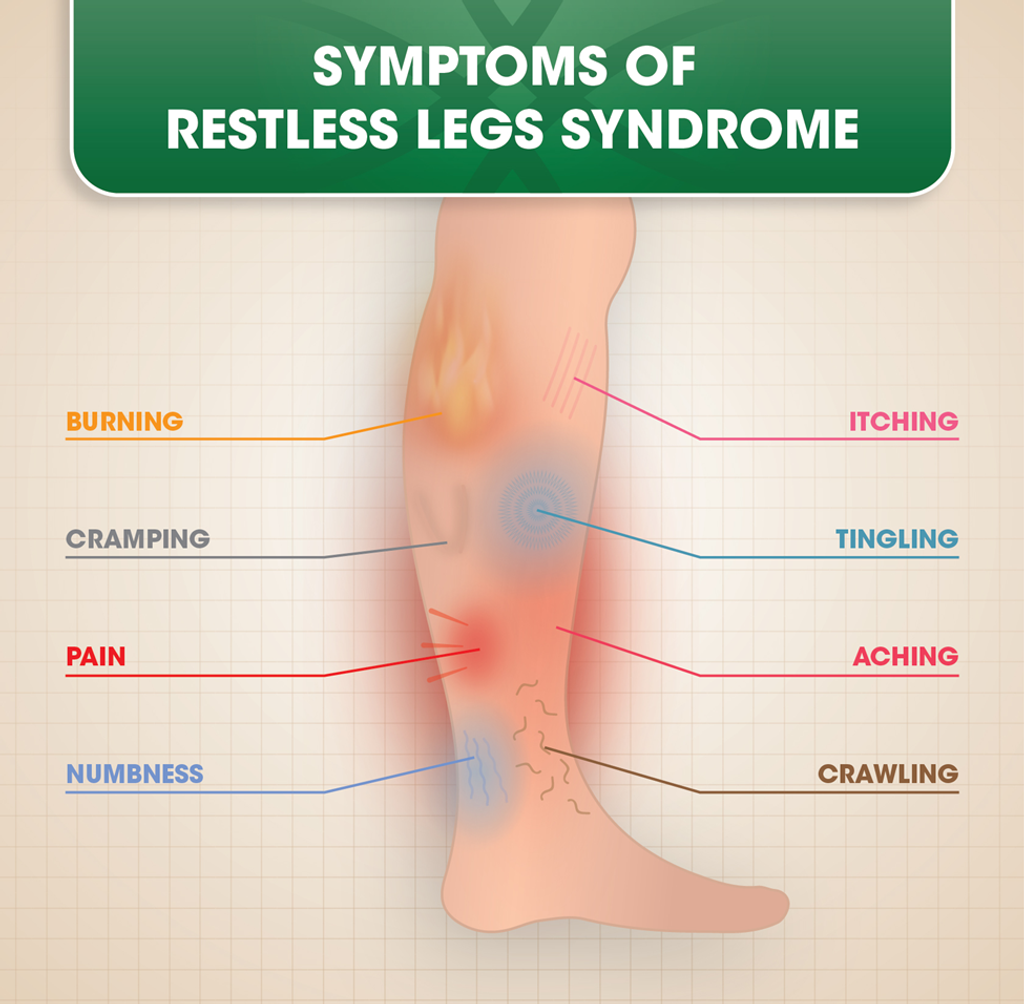

Restless leg syndrome (RLS) is a prevalent, long-standing condition that primarily affects the lower limbs. It is characterized by an uncontrollable urge to move the legs. Symptoms typically worsen during periods of rest in the evening and subside or disappear when the individual starts walking or moving their legs [1]. The underlying mechanisms of this disorder remain unclear. However, evidence indicates that iron deficiency may play a significant role in the onset and progression of RLS, potentially disrupting the function of dopaminergic and serotoninergic systems in the brain and spinal cord. Moreover, RLS is more commonly observed in individuals with chronic renal failure, anemia, and during pregnancy [2].

Research has demonstrated that medications affecting the dopaminergic system can impact the development and severity of RLS [3]. Metoclopramide is a potent dopaminergic antagonist targeting the D2-subtype dopamine receptor (D2R). The FDA approved it for managing nausea and vomiting in patients with conditions like gastroesophageal reflux disease or diabetic gastroparesis, and it is also utilized for combating chemotherapy-induced vomiting [4].

Notably, the onset or worsening of RLS has been documented as a recognized adverse effect of intravenous (IV) metoclopramide [5]. Moreover, prolonged usage of metoclopramide can precipitate movement disorders such as tardive dyskinesia and Parkinsonism, with dystonia and akathisia potentially emerging even after a single dose [6]. Nevertheless, instances of RLS following oral administration of metoclopramide are seldom reported.

This case report details the experience of a male patient who experienced sudden symptoms of RLS after receiving a second dose of oral metoclopramide, which had been prescribed to alleviate side effects associated with semaglutide.

Case Presentation

- Patient Presentation

- A 33-year-old male visited our clinic with severe nausea and vomiting, persisting for two days.

- He had recently commenced taking semaglutide 0.25 mg for weight loss.

- No other complaints were reported upon presentation, and abdominal and neurological examinations were normal.

- Suspecting a drug adverse effect due to the severity and context of gastrointestinal symptoms, semaglutide was discontinued.

- Treatment and Symptom Development

- Before discharge, oral metoclopramide therapy (10 mg, twice daily) was initiated to manage vomiting and nausea.

- However, following the third dose of metoclopramide, the patient experienced an unusual sensation in his legs, characterized by an irresistible urge to move them and accompanied by painful and unsettling “creepy crawly” sensations, particularly during rest.

- Notably, vigorous leg movements provided temporary relief, while cessation of movement exacerbated the symptoms.

- The patient reported no associated symptoms of anxiety or restlessness.

- Family History and Laboratory Workup

- The patient’s family history revealed chronic RLS in one brother without specific triggers.

- Extensive laboratory tests, including complete blood count and various metabolic and hormonal profiles (Table 1), showed no abnormalities.

- There was no history of iron-deficiency anemia or chronic renal disease.

Table 1: Patient’s clinical and biological characteristics

BMI: body mass index, MCV: mean corpuscular volume, MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin, TLC: total leucocyte count, CRP: C-reactive protein, HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin, BUN: blood urea nitrogen, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase, TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone, LDH: lactate dehydrogenase, kg/m2: kilogram per square meter, bpm: beats per minute, mmHg: millimeters of mercury, g/dL: grams per deciliter, fL: femtoliters, pg: picograms, mg/dl: milligrams per deciliter, mmoL/L: millimoles per liter, U/L: units per liter, pg/mL: picograms per milliliter, ng/dL: nanograms per deciliter, uIU/mL: micro-international units per milliliter, ug/dL: micrograms per deciliter, ng/mL: nanograms per milliliter.

- Discontinuation of Oral Metoclopramide

- Following discontinuation of oral metoclopramide, symptoms completely resolved within 48 hours, indicating a potential drug-induced episode of RLS.

- Follow-up Assessments

- Subsequent evaluations at three and six-months post-discontinuation showed no recurrence of symptoms, suggesting sustained resolution.

Discussion

This case underscores the rarity of oral metoclopramide-induced RLS in a patient lacking a prior history of RLS and with normal laboratory findings. The temporal relationship between initiating oral metoclopramide and the subsequent onset and resolution of RLS symptoms upon discontinuation strongly suggests a causal connection.

The occurrence of RLS associated with oral metoclopramide therapy is infrequently documented in current literature, whereas there are several reported cases linked to its injectable form. Sieminski and Zemojtel previously published a case report concerning a 32-year-old woman with migraine who experienced RLS symptoms after receiving IV metoclopramide for migraine-associated vomiting. Management involved discontinuation of treatment along with an intensive saline infusion, resulting in sustained symptom resolution [7]. In another instance, Moos & Hansen reported a case of akathisia (resembling RLS) following a single preoperative dose of 10 mg metoclopramide [6]. Similarly, Ibiloglu documented an episode of akathisia secondary to short-term metoclopramide use in a 56-year-old male with gastroesophageal reflux disease [8], while Qiu and Lim described acute akathisia in a young woman receiving an IV bolus for gastroenteritis treatment [9]. Other cases of iatrogenic RLS associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., citalopram) have also been reported [10].

From a mechanistic perspective, metoclopramide has the potential to induce RLS and other movement disorders by interfering with the extrapyramidal dopaminergic and cholinergic systems [6]. Through its activity on the D2 subtype dopamine receptor (D2R), metoclopramide acts as an antagonist to dopamine in the central nervous system, potentially leading to disinhibition and facilitating acute episodes of movement disorders. Experimental evidence in mice has shown that unilateral striatal injection of metoclopramide can induce inversive turning behavior [11]. Additionally, studies have demonstrated decreased D2R expression in white blood cells during RLS [12].

Pharmacological investigations have revealed that dopamine agonists can alleviate RLS symptoms, whereas dopamine antagonists may exacerbate them [3]. Dyskinesia has been proposed as an idiosyncratic reaction to metoclopramide [13], suggesting a similar possibility for RLS. The rarity of metoclopramide-associated movement disorders [13] indicates that only a specific subset of patients may develop an RLS-like reaction. A family history of RLS in a first-degree relative of our patient strongly implies potential familial susceptibility. This susceptibility may be accompanied by inherent processes predisposing individuals to these episodes.

Furthermore, genetic variations in CYP2D6 enzymes have been found to influence the pharmacokinetics of metoclopramide [14], potentially altering its pharmacodynamics by increasing its brain bioavailability and thus exposing patients to adverse reactions.

This case underscores the significance of recognizing medication-induced RLS in individuals who exhibit newfound compulsive leg sensations and movement disorders, especially following recent medication commencement. What makes this case noteworthy is the manifestation of this adverse effect after the oral administration of metoclopramide. Hence, it is imperative to meticulously evaluate the medication history of patients experiencing new-onset movement disorders while on metoclopramide or medications with similar mechanisms of action. Upon suspicion of a metoclopramide-induced RLS-like reaction, treatment interruption is warranted, and the avoidance of other dopamine antagonists may be advisable in the long term.

Conclusions

This case study reveals RLS as a potentially yet less common adverse outcome of oral metoclopramide, contrasting with its intravenous counterpart. The noteworthy aspect of this reaction is its benign and swiftly reversible nature upon cessation of treatment, underscoring the significance of monitoring RLS symptoms in patients prescribed oral metoclopramide. This discovery highlights the diversity of drug side effects across various administration routes and emphasizes the importance of vigilant patient monitoring in pharmacotherapy. On a broader scale, this case serves as a reminder of the dynamic and occasionally unpredictable nature of drug reactions, emphasizing the necessity for ongoing vigilance in pharmacotherapy.

References

- Mansur A, Castillo PR, Rocha Cabrero F, Bokhari SR: Restless legs syndrome. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); 2024.

- Amir A, Masterson RM, Halim A, Nava A: Restless leg syndrome: pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, and treatment. Pain Med. 2022, 23:1032-5. 10.1093/pm/pnab253

- Comella CL: Restless legs syndrome: treatment with dopaminergic agents. Neurology. 2002, 58:87-92. 10.1212/wnl.58.suppl_1. s87

- Isola S, Hussain A, Dua A, Singh K, Adams N: Metoclopramide. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); 2024.

- Hoque R, Chesson AL Jr: Pharmacologically induced/exacerbated restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements of sleep, and REM behavior disorder/REM sleep without atonia: literature review, qualitative scoring, and comparative analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010, 6:79-83.

- Moos DD, Hansen DJ: Metoclopramide and extrapyramidal symptoms: a case report. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008, 23:292-9. 10.1016/j.jopan.2008.07.006

- Sieminski M, Zemojtel L: Acute drug-induced symptoms of restless legs syndrome in an emergency department. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019, 15:779-80. 10.5664/jcsm.7774

- Ibiloglu AO: Metoclopramide induced akathisia: a case report. Bull Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013, 23:187-90.

- Qiu LM, Lim BL: Case of acute akathisia from intravenous metoclopramide. Singapore Med J. 2011, 52:12-4.

- Perroud N, Lazignac C, Baleydier B, Cicotti A, Maris S, Damsa C: Restless legs syndrome induced by citalopram: a psychiatric emergency? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007, 29:72-4. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.10.006

- Peringer E, Jenner P, Donaldson IM, Marsden CD, Miller R: Metoclopramide and dopamine receptor blockade. Neuropharmacology. 1976, 15:463-9.

- Mitchell UH, Obray JD, Hunsaker E, Garcia BT, Clarke TJ, Hope S, Steffensen SC: Peripheral dopamine in restless legs syndrome. Front Neurol. 2018, 9:155. 10.3389/fneur.2018.00155

- Rao AS, Camilleri M: Review article: metoclopramide and tardive dyskinesia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010, 31:11-9. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009. 04189.x

- Bae JW, Oh KY, Yoon SJ, et al.: Effects of CYP2D6 genetic polymorphism on the pharmacokinetics of metoclopramide. Arch Pharm Res. 2020, 43:1207-13. 10.1007/s12272-020-01293-4

About Docquity

If you need more confidence and insights to boost careers in healthcare, expanding the network to other healthcare professionals to practice peer-to-peer learning might be the answer. One way to do it is by joining a social platform for healthcare professionals, such as Docquity.

Docquity is an AI-based state-of-the-art private & secure continual learning network of verified doctors, bringing you real-time knowledge from thousands of doctors worldwide. Today, Docquity has over 400,000 doctors spread across six countries in Asia. Meet experts and trusted peers across Asia where you can safely discuss clinical cases, get up-to-date insights from webinars and research journals, and earn CME/CPD credits through certified courses from Docquity Academy. All with the ease of a mobile app available on Android & iOS platforms!