Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a rare condition stemming from uncontrolled complement activation due to complement dysregulation. It typically arises from various triggers such as infections, inflammation, pregnancy, or medications. Dengue, a viral disease endemic to Southeast Asia, can activate the complement pathway, potentially leading to aHUS in genetically predisposed individuals. We present the case of a 33-year-old man who initially presented with Dengue fever and subsequently developed aHUS. Plasma exchange (PLEX) effectively restored his neurological status and hematological parameters. While his renal function improved, it did not fully recover. Eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting C5, was administered for six months. Successfully discontinuing the treatment without signs of relapse after six months of follow-up highlights the safety of this approach in patients lacking pathogenic mutations or variants in complement factors.

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS): Introduction

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is an extremely rare condition, with an annual prevalence ranging from 0.29 to 1.9 per million population [1]. It is characterized by thrombotic microangiopathy, which result in end-organ damage due to complement dysregulation [2]. Eculizumab, the preferred treatment for aHUS, was previously considered to necessitate lifelong administration, which poses significant financial challenges. However, recent evidence suggests that a more cost-effective and time-limited approach to Eculizumab may be suitable for low-risk patients. In this case, we present a patient with aHUS triggered by a dengue infection, successfully managed with a finite course of Eculizumab treatment.

Case Presentation

- Patient Information: A 33-year-old male was admitted for dengue fever.

- Initial Presentation

- Symptoms: Fever and myalgia.

- Profound thrombocytopenia was observed.

- Hemoglobin: 15.4 g/dL (normal: 14-16.5 g/dL).

- Platelet count: 20 x 10^9/L (normal: 150-450 x 10^9/L).

- Creatinine: 200 µmol/L (normal: 59-104 µmol/L).

- Confirmed Diagnosis

- Positive dengue antigen testing (NS-1).

- Positive dengue serology tests (IgM and IgG).

- Subsequent Events

- Day 2: Developed massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to a gastric ulcer.

- Required intubation, endoscopic hemostasis, and transfusion.

- Condition improved post-hemostasis.

- Day 5: Experienced altered mental state, worsening thrombocytopenia, renal function decline, and Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia.

- Hemoglobin dropped to 6.3 g/dL.

- Platelets reduced to 31 x 10^9/L.

- Creatinine increased to 400 µmol/L.

- Positive hemolysis screen:

- Elevated bilirubin: 40 µmol/L (normal <21 µmol/L).

- Low haptoglobin: <0.1 g/L (normal: 0.3-2.0 g/L).

- Raised LDH: 554 U/L (normal 222-454 U/L).

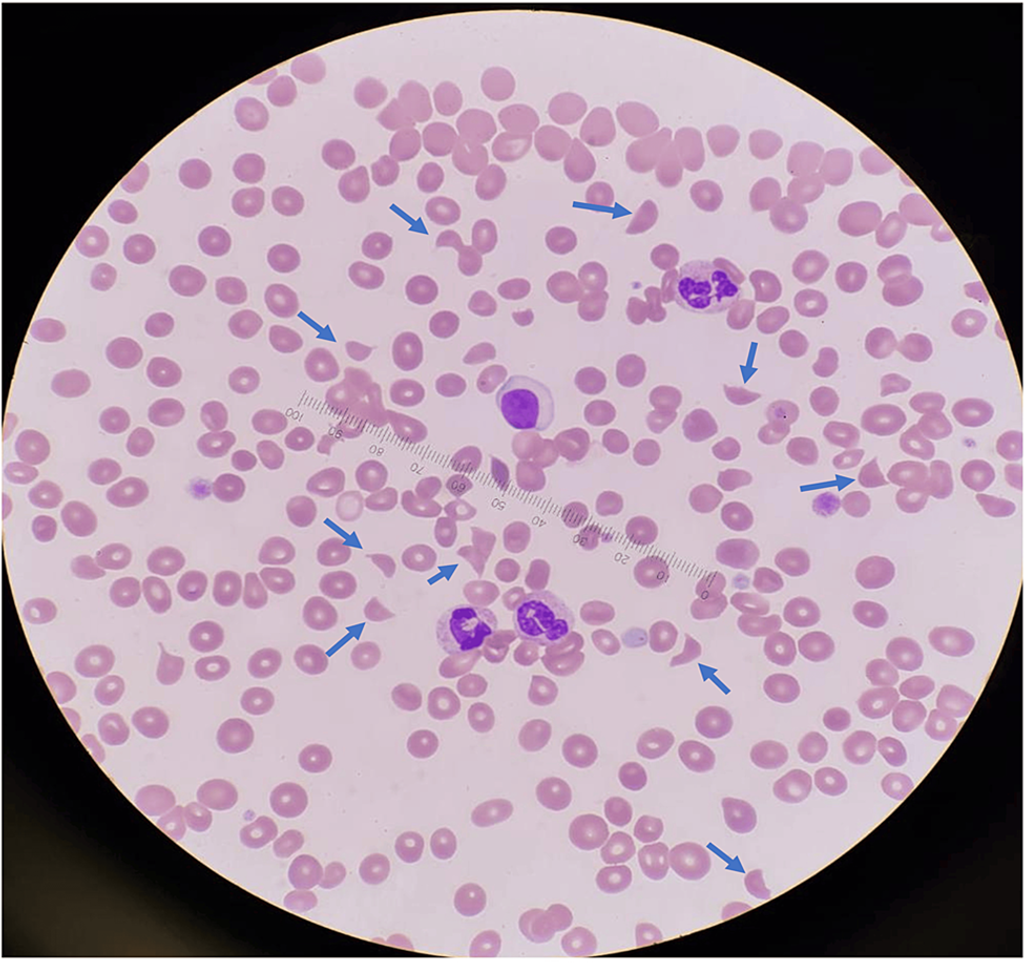

- Blood film showed numerous schistocytes, as shown in Figure 1.

- Day 2: Developed massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to a gastric ulcer.

Figure 1: Peripheral blood film at diagnosis showing markedly elevated schistocytes (10 per high-power field, indicated by blue arrows) and thrombocytopenia, observed under 100x oil immersion.

- Initial Treatment Approach

- Initially managed as presumptive thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).

- Prompt initiation of plasma exchange (PLEX).

- Response to Treatment

- Two days post-PLEX initiation: Resolution of confusion, platelet count improved to 53 x 10^9/L without further transfusions.

- Confirmation and Reassessment

- The subsequent return of ADAMTS13 level to normal (47%) ruled out TTP.

- Exclusion of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) infection via negative stool culture.

- Revised Diagnosis

- Diagnosis of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) triggered by dengue fever.

- Treatment Continuation

- Daily continuation of PLEX, leading to platelet count normalization by day 12.

- Frequency reduction to every other day post-platelet count normalization, eventually tapering to twice a week within five weeks.

- Clinical Progress

- Despite the rapid hematological response, renal response lagged.

- Creatinine returned to pre-PLEX levels four weeks post-PLEX initiation (creatinine 150 µmol/L at steady state).

- Consideration of Alternative Treatment

- Eculizumab was considered but not pursued due to its high cost.

- Subsequent Events

- Developed disseminated Mycobacterium abscessus septicemia after 3.5 months on PLEX.

- Required admission for prolonged combination antibiotics.

- Genetic Mutation Analysis

- A heterozygous variant of uncertain significance was detected in the CFHR3 gene (CFHR3c.115C>T, p. Arg39Cys).

- The mutation’s pathogenicity is currently unknown.

- Treatment Adjustment

- Initiation of Eculizumab, simultaneous discontinuation of PLEX.

- Follow-Up

- No clinical or laboratory evidence of relapse was observed six months post-eculizumab discontinuation.

Discussion

aHUS predominantly impacts blood and kidney function, with over 50% of patients progressing to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [3]. Additionally, it affects various other bodily systems, including neurological (48%), cardiovascular (43%), and gastrointestinal (30%) systems, as well as the pulmonary and ocular systems. The symptoms of aHUS are diverse and nonspecific, posing challenges for diagnosis [3].

Viral infections such as dengue can activate complement pathways, potentially triggering aHUS in individuals with genetic predispositions [4]. This case likely involves a secondary dengue infection, as positive dengue IgG and IgM serologies indicate. Notably, dengue comprises four serotypes, and prior infection with one serotype does not provide immunity against others. Secondary dengue infections, commonly associated with different serotypes, often manifest more severe symptoms due to heightened complement activation, particularly within the alternative pathway [5]. Although the heterozygous variant detected in the CFH gene in patient lacked known pathogenicity based on current literature, he may still have been genetically predisposed (first hit). The secondary dengue infection could have acted as the second hit event, leading to uncontrolled complement activation and the onset of aHUS.

The case fulfilled all the laboratory criteria commonly adopted in trials for diagnosing aHUS [6,7]. Firstly, evidence of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) was apparent, characterized by elevated LDH, reduced haptoglobin, thrombocytopenia, and schistocytes (Figure 1). While schistocytes in the blood film support a TMA diagnosis, they are not mandatory if the overall clinical presentation aligns with TMA [7]. Secondly, notable renal dysfunction was observed. Thirdly, aHUS mimics such as STEC-related HUS and TTP were ruled out.

Despite guidelines recommending screening for CFH, Membrane Cofactor Protein (MCP/CD46), Complement Factor I (CFI), Complement factor B (CFB), Complement 3 (C3), Thrombomodulin (THBD), and CFH antibody to confirm complement pathway dysregulation [4], none of these tests were conducted due to unavailability in Singapore (except for C3). Additionally, quantitatively normal CF levels do not necessarily indicate normal functionality [4]. Only 22% of patients with CFH mutations exhibit low CFH levels, while 37% have normal levels [4]. Establishing a normal range for CFH and CFI is challenging due to significant variations across different age groups [4]. Importantly, similar to ADAMTS13, these tests can be affected by PLEX and should be strictly collected before initiating PLEX.

Genetic mutation analysis is an integral part of the diagnostic evaluation for aHUS [4]. Over 50% of individuals with aHUS exhibit genetic mutations within the complement system, with CFH mutations being the most prevalent (24%), followed by MCP (7%), CFI, C3, and THBD mutations (3-4%) [4]. Identifying heterozygous/homozygous pathogenic variants confirms the diagnosis of aHUS, although non-pathogenic variants, as observed in patients, do not exclude aHUS. These genetic studies serve additional purposes, including prognostication, determining treatment duration, and predicting response to PLEX. For instance, MCP (CD46) mutations are associated with the most favorable renal outcomes and mortality benefits, whereas CFH or THBD mutations are linked to poorer renal transplant outcomes. PLEX induces remission in 55-80% of episodes in patients with autoantibody H, CFH, C3, and THBD mutations, but individuals with CFI mutations tend to respond poorly [2]. PLEX achieves remission by replacing non-membrane-bound plasma proteins (e.g., CFH, C3) and eliminating Antibody H. This elucidates the favorable response to PLEX observed in the case of the CFHR3 variant.

However, upon long-term follow-up, it was revealed that 78% of patients had either succumbed to mortality or progressed to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) despite prolonged PLEX therapy [3]. Therefore, while PLEX proves productive as an initial intervention, its indefinite utilization for aHUS is not advisable.

Eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody, operates by obstructing C5 cleavage, thereby impeding the generation of the proinflammatory peptide C5a and the C5b-9 membrane attack complex, pivotal in the pathogenesis of aHUS [6]. It can facilitate renal function and normalize hematological parameters in 76% and 88% of patients, respectively [6]. Despite its efficacy, Eculizumab has encountered limited utilization due to its substantial cost. Initially marketed as a lifelong regimen, recent research findings have showcased that discontinuing Eculizumab in patients lacking pathogenic variants, following a finite period of 3-6 months, yields a low relapse rate averaging at 3.5% [8,9]. This shift has facilitated significant cost reductions and heightened the adoption rate of Eculizumab.

The patient’s CFH3 variant presently lacks classification as a recognized pathogenic mutation/variant, so funding was secured for six months of Eculizumab therapy. Despite exhibiting favorable neurological and hematological responses, renal function normalization remained elusive despite Eculizumab administration. This delay in initiating Eculizumab, attributable to financial constraints, might underlie the suboptimal renal outcome. A post hoc analysis by Walle JV et al. demonstrated enhanced renal outcomes if Eculizumab could be initiated within seven days of diagnosis [10].

Conclusions

In genetically predisposed individuals, dengue has the potential to induce aHUS. Although PLEX serves as an efficacious initial therapy in patients without mutations in the CFI gene, its sustained benefits over the long term are lacking. Conversely, Eculizumab surpasses PLEX in yielding improved renal outcomes and reducing mortality risks. It is advisable to initiate Eculizumab promptly, preferably within seven days of diagnosis, and maintain treatment for 3-6 months in individuals lacking pathogenic variant mutations. This strategy not only achieves cost savings but also preserves treatment efficacy.

References

- Tan Y, Teo E, Ng H (April 22, 2024) A Rare Case of Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (aHUS) Precipitated by Dengue and the Treatment Landscape in Singapore. Cureus 16(4): e58731. doi:10.7759/cureus.58731

- Yan K, Desai K, Gullapalli L, Druyts E, Balijepalli C: Epidemiology of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a systematic literature review. Clin Epidemiol. 2020, 12:295-305. 10.2147/CLEP.S245642

- Noris M, Caprioli J, Bresin E, et al.: Relative role of genetic complement abnormalities in sporadic and familial aHUS and their impact on clinical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010, 5:1844-1859. 10.2215/CJN.02210310

- Caprioli J, Noris M, Brioschi S, et al.: Genetics of HUS: the impact of MCP, CFH, and IF mutations on clinical presentation, response to treatment, and outcome. Blood. 2006, 108:1267-1279. 10.1182/blood-2005-10-007252

- Taylor CM, Machin S, Wigmore SJ, Goodship TH: Clinical practice guidelines for the management of atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome in the United Kingdom. Br J Haematol. 2010, 148:37-47. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009. 07916.x

- Cabezas S, Bracho G, Aloia AL, et al.: Dengue virus induces increased activity of the complement alternative pathway in infected cells. J Virol. 2018, 92:10.1128/JVI.00633-18

- Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, et al.: Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013, 368:2169-2181. 10.1056/NEJMoa1208981

- Lee H, Kang E, Kang HG, et al.: Consensus regarding diagnosis and management of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Korean J Intern Med. 2020, 35:25-40. 10.3904/kjim.2019.388

- Brodsky RA: Eculizumab and aHUS: to stop or not. Blood. 2021, 137:2419-2420. 10.1182/blood.2020010234

- Fakhouri F, Fila M, Hummel A, et al.: Eculizumab discontinuation in children and adults with atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome: a prospective multicenter study. Blood. 2021, 137:2438-2449. 10.1182/blood.2020009280

- Walle JV, Delmas Y, Ardissino G, Wang J, Kincaid JF, Haller H: Improved renal recovery in patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome following rapid initiation of eculizumab treatment. J Nephrol. 2017, 30:127-134. 10.1007/s40620-016-0288-3

About Docquity

If you need more confidence and insights to boost careers in healthcare, expanding the network to other healthcare professionals to practice peer-to-peer learning might be the answer. One way to do it is by joining a social platform for healthcare professionals, such as Docquity.

Docquity is an AI-based state-of-the-art private & secure continual learning network of verified doctors, bringing you real-time knowledge from thousands of doctors worldwide. Today, Docquity has over 400,000 doctors spread across six countries in Asia. Meet experts and trusted peers across Asia where you can safely discuss clinical cases, get up-to-date insights from webinars and research journals, and earn CME/CPD credits through certified courses from Docquity Academy. All with the ease of a mobile app available on Android & iOS platforms!