Exploding head syndrome, a benign and often overlooked sensory parasomnia, manifests as the perception of a sudden loud noise during transitions between wakefulness and sleep. This article discusses the assessment and treatment of exploding head syndrome and emphasizes the collaborative efforts of healthcare teams in caring for individuals affected by this condition.

Objectives

- Explore the underlying causes contributing to exploding head syndrome.

- Outline the characteristic symptoms observed in individuals experiencing exploding head syndrome.

- Discuss the standard approaches to managing patients diagnosed with exploding head syndrome.

- Emphasize the significance of teamwork and effective communication among healthcare professionals in accurately diagnosing and treating patients afflicted by exploding head syndrome.

Introduction to Exploding Head Syndrome

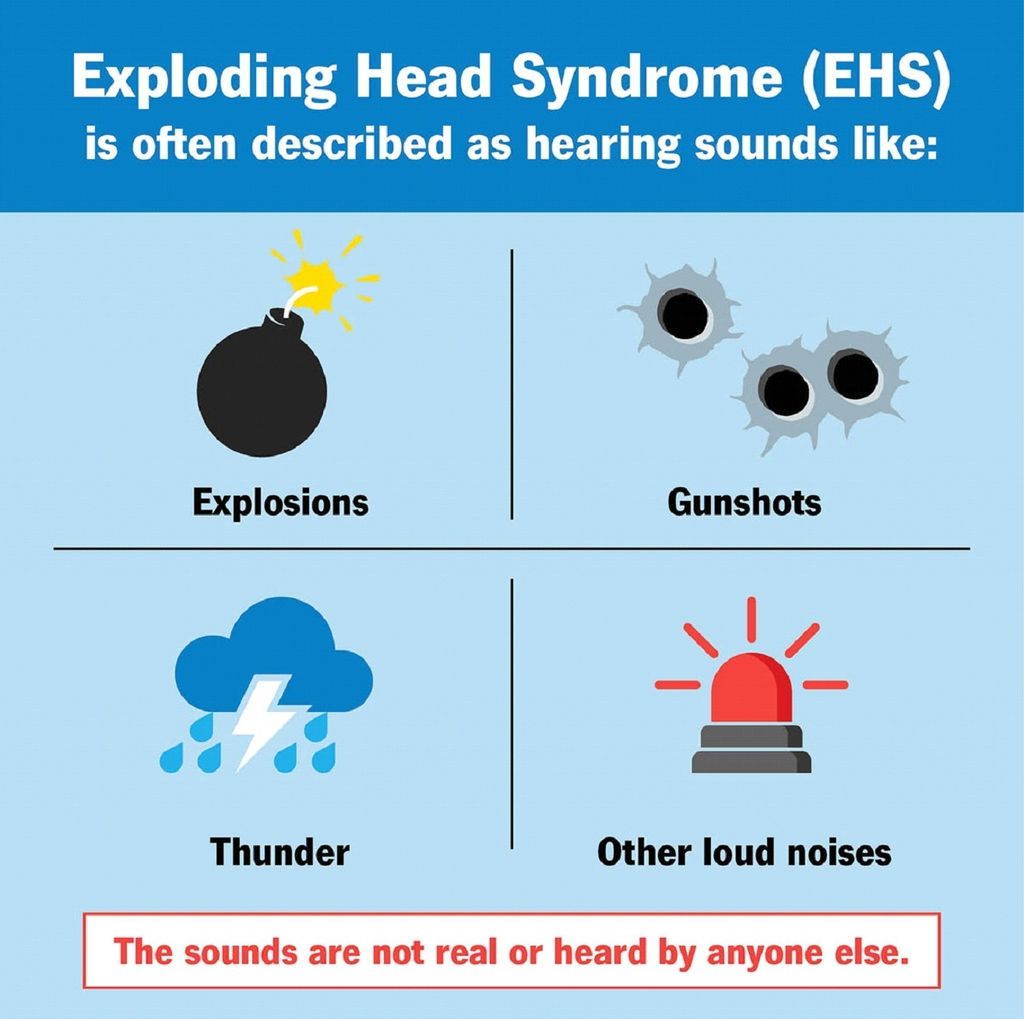

Exploding head syndrome (EHS) is a benign parasomnia marked by the sensation of hearing a loud noise while asleep, resulting in sudden awakening. These incidents typically occur during the transition between wakefulness and sleep or vice versa, lasting briefly, usually less than a second [1]. Accompanying these episodes may be flashes of light and distress in the individual, yet there is typically no significant associated pain [2,3]. While the perceived sounds are often likened to explosions, gunshots, or thunder, they can encompass nearly any loud noise [3]. The frequency of these occurrences varies, with intermittent periods of remission between episodes [4].

In 1876, American neurologist Silas Weir Mitchell documented the first instance of exploding head syndrome (EHS) in medical literature. Mitchell presented a case study involving two patients who experienced nocturnal sensations of loud sounds, which he termed “sensory shocks.” [5] Despite earlier accounts and case reports of EHS, it was not officially recognized as a sleep disorder until 2005, when it was included in the 2nd edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-2) [6]. Recently, the term “episodic cranial shock” has been suggested as an alternative descriptor for this phenomenon [5].

The phenomenon can be alarming to those unaware of its harmless nature. Patients may initially suspect more serious causes for the sounds, such as a stroke, brain tumor, or brain hemorrhage, leading many to seek medical evaluations. EHS remains underdiagnosed and underreported, partly because patients may feel embarrassed about their symptoms, and healthcare providers may lack familiarity with the condition[1].

Etiology

The definite etiology of EHS has not been determined, yet researchers have proposed the following hypotheses:

- A delayed reduction in reticular formation activity during the wakefulness-to-sleep transition leads to a transient surge in sensory neuron activity [7].

- Occurrence of complex partial seizures originating in the temporal lobe [8].

- Ear Pathology [3]:

- Dysfunction of the Eustachian tube

- Fistulas in the perilymph

- Tear in the round window membrane.

- Temporary loss of inhibition in the cochlea or its central connections in the temporal lobe

- Sudden involuntary movement of the eardrum or tensor tympani

- Anomalous attentional processing during the transition between wakefulness and sleep leads to a modified perception of external auditory or visual stimuli [4].

- Pre-migraine sensory disturbance is known as an aura [9,10,11].

- Adverse effects stemming from sudden discontinuation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or benzodiazepines [12].

- Genetic mutation leads to temporary dysfunction of calcium channels [13].

Epidemiology

As the majority of journal articles regarding EHS contain case reports, precise prevalence rates remain elusive [3]. Although no clear gender predominance has been established, several studies suggest a higher incidence of EHS in females than males [1,7]. Initially perceived as a rare disorder primarily affecting middle-aged women, recent research indicates that EHS may be more widespread across all age groups than previously presumed [9]. One study found that up to 16% of college students reported experiencing EHS events [2,7]. Older adults are more inclined to report symptoms without prompting, possibly due to anxiety related to age-related intracranial conditions [14].

EHS seems to occur more frequently among individuals diagnosed with isolated sleep paralysis [15]. In one study, nearly 37% of participants with a history of sleep paralysis reported experiencing EHS symptoms at least once [7]. While there is no uniform trigger, some patients have noted a correlation between heightened event frequency and insomnia or periods of elevated stress [2]. Additionally, hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations, nightmares, and lucid dreaming may coincide with EHS occurrences [16].

History and Physical

As outlined in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition (ICSD-3), the diagnostic criteria for exploding head syndrome include the following [3]:

- There has been a report of a sudden, loud noise perceived in the head upon awakening at night or during the transition between wakefulness and sleep.

- Prompt and distressing arousal following the occurrence.

- Absence of significant pain accompanying the sensation.

Episodes of EHS are more commonly reported during the transition from wakefulness to sleep than from sleep to waking. Flashes of light, hypnic jerks, and physiological manifestations of fear such as sweating, palpitations, and shortness of breath may accompany these events [3]. Notably, there is typically no significant pain associated with EHS episodes, and any reported pain may be attributed to the shock or fear experienced during the event [3]. Therefore, complaints of pain should prompt further evaluation to rule out alternative diagnoses.

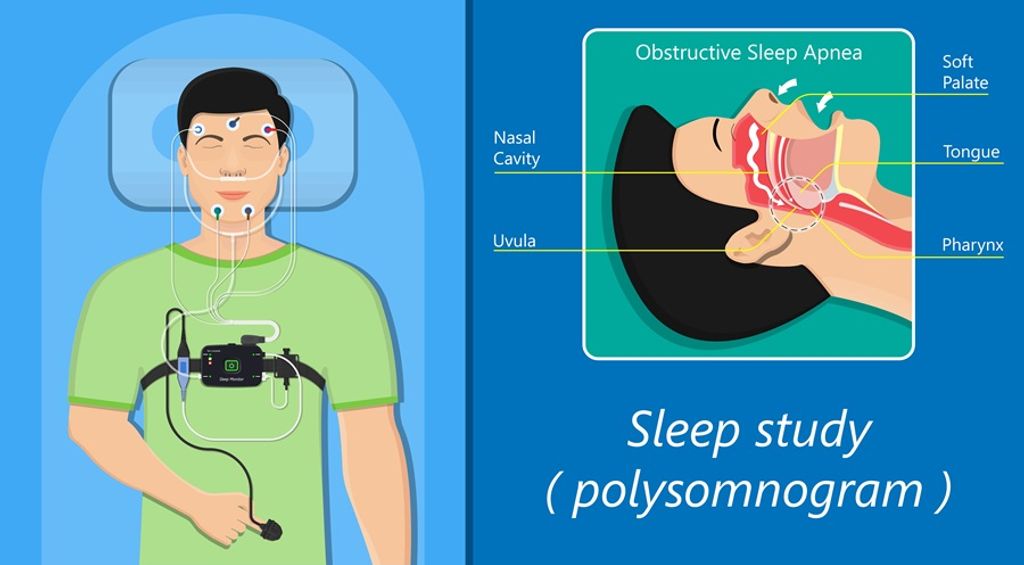

In assessing EHS, physicians should inquire about other sleep disorders, medical conditions, and psychiatric conditions, as these may uncover comorbidities such as sleep apnea [15]. Notably, there is a notable association between EHS and sleep paralysis and insomnia, with EHS potentially serving as a precursor for insomnia [2]. Additionally, a psychological evaluation may reveal underlying stress or anxiety contributing to EHS episodes [17]. Physical examination findings are typically unremarkable, with a normal neurological examination.

Evaluation

Currently, no objective tests are available to diagnose EHS. Diagnosis relies on clinical assessment using the criteria outlined in the ICSD-3 [2]. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain typically reveals normal findings, but ambulatory electroencephalography does not detect any epileptiform activity [8].

Polysomnography:

- Normal sleep duration and structure [17,18].

- Events are most likely to occur during transitions from wakefulness to N1 sleep stage and from N1 to wakefulness, although occurrences during awakenings from N2 have also been documented [18].

- In one study, patients exhibited predominantly alpha waves during events, despite the perception of being asleep, with interspersed theta activity [8].

- Absence of epileptiform activity [18].

- Another study noted additional oscillatory activity alongside the alpha waves during events but originating from a different source and frequency[4].

Treatment & Management

The main approach to managing EHS involves educating patients and reassuring them regarding the harmless nature of the condition [14]. Reassurance alone can reduce the frequency of attacks. Additionally, managing anxiety may help decrease the occurrence of episodes [17,18]. Identifying and addressing stress triggers, maintaining regular and healthy sleep patterns, and addressing concurrent sleep disorders are crucial management aspects [2].

There is a lack of research or clinical trials examining pharmaceutical interventions for treating EHS [14]. However, in cases where symptoms are significantly distressing and non-pharmacological interventions prove ineffective, certain medications have been reported to be effective in reducing symptoms, as documented in case reports.

- Clomipramine: All three patients experienced symptom resolution [8].

- Amitriptyline: One patient experienced a frequency reduction, and the other experienced complete remission [14].

- Topiramate: Intensity reduction reported [19].

- Duloxetine Hydrochloride: Frequency and duration of events reduced in one of two patients [17].

- Nifedipine [13].

Differential Diagnosis

- Nocturnal epilepsy: Occurs during NREM sleep; however, unlike EHS, patients do not recollect the events afterward [14].

- Hypnic headaches: They are recurrent headaches during sleep that result in awakening. The associated pain lasts from 15 minutes to four hours, is unilateral or bilateral, and occurs for more than ten days per month for over three months [20]. Compared to headache syndromes, EHS events are distressing rather than painful; any reported pain is typically a minor aspect of the complaint.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and nightmare disorder: Patients with EHS do not recall specific dream content associated with the episodes [14].

Prognosis & Complications

Patients diagnosed with EHS generally have a favorable prognosis, with no reported sequelae [14]. Following initial reassurance, the frequency and intensity of episodes may decrease. Over time, the condition may resolve entirely, and no documented complications are associated with EHS.

Promotion of Awareness and Patient Education

Patients are encouraged to openly communicate unusual sleep occurrences, as they often withhold such complaints due to apprehension of embarrassment [3]. Stress and unmanaged anxiety can serve as potential catalysts for EHS, underscoring the importance of discussing management strategies with healthcare providers [2]. Emphasizing the harmless nature of EHS is vital [14]. Patients commonly experience distress following an episode and may harbor concerns about a severe underlying ailment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Performance

Healthcare providers should actively investigate symptoms suggestive of EHS and include it as a potential diagnostic consideration when assessing patients with atypical sleep complaints [7]. Numerous patients seeking medical consultation have indicated that healthcare professionals lacked familiarity with EHS [16]. This lack of awareness may lead to delayed or incorrect diagnoses and unnecessary testing [3]. Enhancing understanding of this syndrome among healthcare teams is crucial for ensuring accurate diagnoses and alleviating patient anxiety when presenting symptoms are initially reported [16].

References

- Pearce JM. Clinical features of the exploding head syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989 Jul;52(7):907-10.

- Sharpless BA. Characteristic symptoms and associated features of exploding head syndrome in undergraduates. Cephalalgia. 2018 Mar;38(3):595-599.

- Sharpless BA. Exploding head syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2014 Dec;18(6):489-93.

- Fotis Sakellariou D, Nesbitt AD, Higgins S, Beniczky S, Rosenzweig J, Drakatos P, Gildeh N, Murphy PB, Kent B, Williams AJ, Kryger M, Goadsby PJ, Leschziner GD, Rosenzweig I. Co-activation of rhythms during alpha-band oscillations as an interictal biomarker of exploding head syndrome. Cephalalgia. 2020 Aug;40(9):949-958.

- Goadsby PJ, Sharpless BA. Exploding head syndrome, snapping of the brain, or episodic cranial sensory shock? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016 Nov;87(11):1259-1260.

- Otaiku AI. Did René Descartes Have Exploding Head Syndrome? J Clin Sleep Med. 2018 Apr 15;14(4):675-678.

- Sharpless BA. Exploding head syndrome is common in college students. J Sleep Res. 2015 Aug;24(4):447-9.

- Sachs C, Svanborg E. The exploding head syndrome: polysomnographic recordings and therapeutic suggestions. Sleep. 1991 Jun;14(3):263-6.

- Evans RW. Exploding head syndrome followed by sleep paralysis: a rare migraine aura. Headache. 2006 Apr;46(4):682-3.

- Rossi FH, Gonzalez E, Rossi EM, Tsakadze N. Exploding Head Syndrome as Aura of Migraine with Brainstem Aura: A Case Report. 2018 Spring J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 32(2):e34-e36.

- Kallweit U, Khatami R, Bassetti CL. Exploding head syndrome–more than “snapping of the brain”? Sleep Med. 2008 Jul;9(5):589.

- Ganguly G, Mridha B, Khan A, Rison RA. Exploding head syndrome: a case report. Case Rep Neurol. 2013 Jan;5(1):14-7.

- Jacome DE. Exploding head syndrome and idiopathic stabbing headache relieved by nifedipine. Cephalalgia. 2001 Jun;21(5):617-8.

- Frese A, Summ O, Evers S. Exploding head syndrome: six new cases and review of the literature. Cephalalgia. 2014 Sep;34(10):823-7.

- Denis D. Relationships between sleep paralysis and sleep quality: current insights. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018; 10:355-367.

- Denis D, Poerio GL, Derveeuw S, Badini I, Gregory AM. Associations between exploding head syndrome and measures of sleep quality and experiences, dissociation, and well-being. Sleep. 2019 Feb 01;42(2)

- Wang X, Zhang W, Yuan N, Zhang Y, Liu Y. Characteristic symptoms of exploding head syndrome in two male patients. Sleep Med. 2019 May; 57:94-96.

- Feketeova E, Buskova J, Skorvanek M, Mudra J, Gdovinova Z. Exploding head syndrome–a rare parasomnia or a dissociative episode? Sleep Med. 2014 Jun;15(6):728-30.

- Palikh GM, Vaughn BV. Topiramate responsive exploding head syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010 Aug 15;6(4):382-3.

- Starling AJ. Unusual Headache Disorders. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2018 Aug;24(4, Headache):1192-1208.

About Docquity

If you need more confidence and insights to boost careers in healthcare, expanding the network to other healthcare professionals to practice peer-to-peer learning might be the answer. One way to do it is by joining a social platform for healthcare professionals, such as Docquity.

Docquity is an AI-based state-of-the-art private & secure continual learning network of verified doctors, bringing you real-time knowledge from thousands of doctors worldwide. Today, Docquity has over 400,000 doctors spread across six countries in Asia. Meet experts and trusted peers across Asia where you can safely discuss clinical cases, get up-to-date insights from webinars and research journals, and earn CME/CPD credits through certified courses from Docquity Academy. All with the ease of a mobile app available on Android & iOS platforms!