Milk transfusions and the medical history of blood replacement practices highlight a brief and bizarre chapter in the late 19th century when scientists were convinced that milk was the perfect substitute for lost blood.

For most of human history, medical science has been a grim affair. It is only with modern innovations in the scientific process and medical techniques that we have been able to accurately determine the efficacy of medical treatments in a safe and scientifically sound manner.

This was not always the case, particularly when it came to blood transfusions. Prior to the discovery of blood types by Karl Landsteiner in 1901 and the development of effective methods to avoid coagulation during transfusions, individuals who had lost significant amounts of blood faced dire prospects. This was compounded not just by the loss of blood itself but by the hazardous substances used in attempts to replace it.

The Early Days of Transfusions

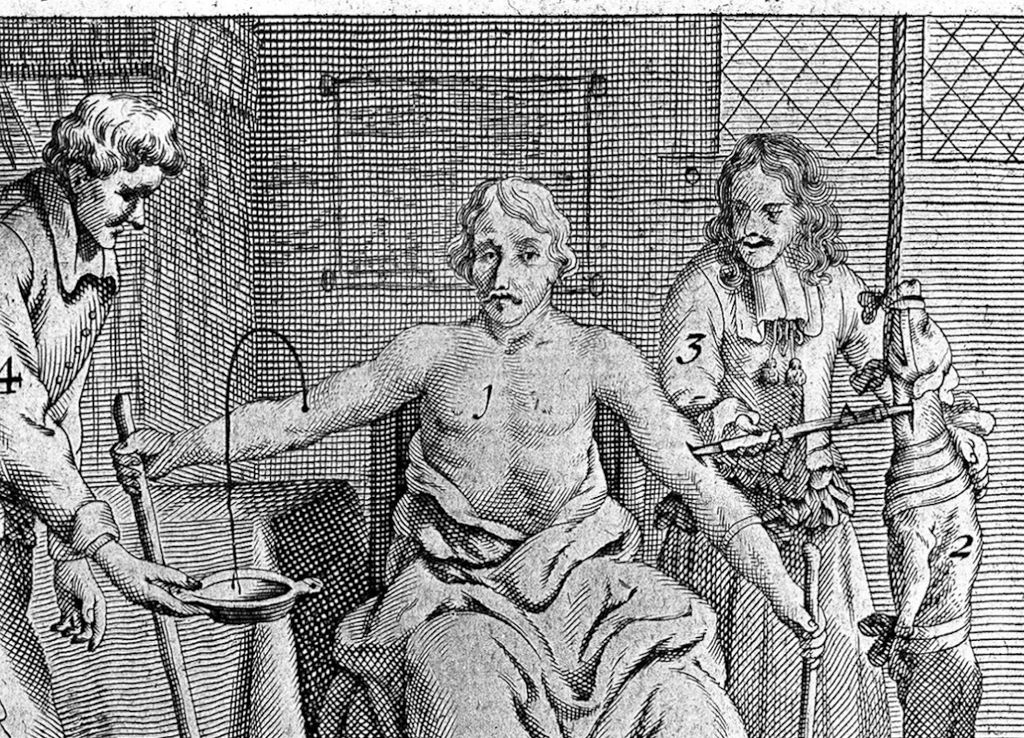

The first successful blood transfusion was performed in the 17th century by a physician named Richard Lower. He had developed a technique that enabled him to transfer blood without excess coagulation in the process, which he demonstrated when he bled a dog and then replaced its lost blood with that from a larger mastiff, who died in the process. Aside from being traumatized and abused, the receiving dog recovered with no apparent ill effects. Lower later transfused lamb blood into a mentally ill individual with the hope that the gentle lamb’s temperament would ease the man’s insanity. The man survived; his mental illness persisted.

In 1667, Jean-Baptiste Denys transfused the blood of a sheep into a 15-year-old boy and a laborer, both of whom survived. Denys and his contemporaries chose not to perform human-to-human transfusions since the process often killed the donor. Despite their initial successes, which likely only occurred due to the small quantities of blood involved, the later transfusions made by these physicians did not go so well. Denys, in particular, became responsible for the death of the Swedish Baron Gustaf Bonde and that of a mentally ill man named Antoine Mauroy.

Ultimately, these experiments were condemned by the Royal Society, the French government, and the Vatican by 1670. Research into blood transfusion stopped for 150 years. The practice had a brief revival in the early 19th century. However, there had been no progress — many of the same problems were still around, like the difficulty of preventing blood from clotting and the recipients’ annoying habits of dying after their lives had just been saved by a blood transfusion. How best to get around blood’s pesky characteristics?

By the mid-19th century, physicians believed they had an answer: Don’t use blood but a blood substitute. Milk seemed like the perfect choice.

The Rise and Fall of Milk Transfusions

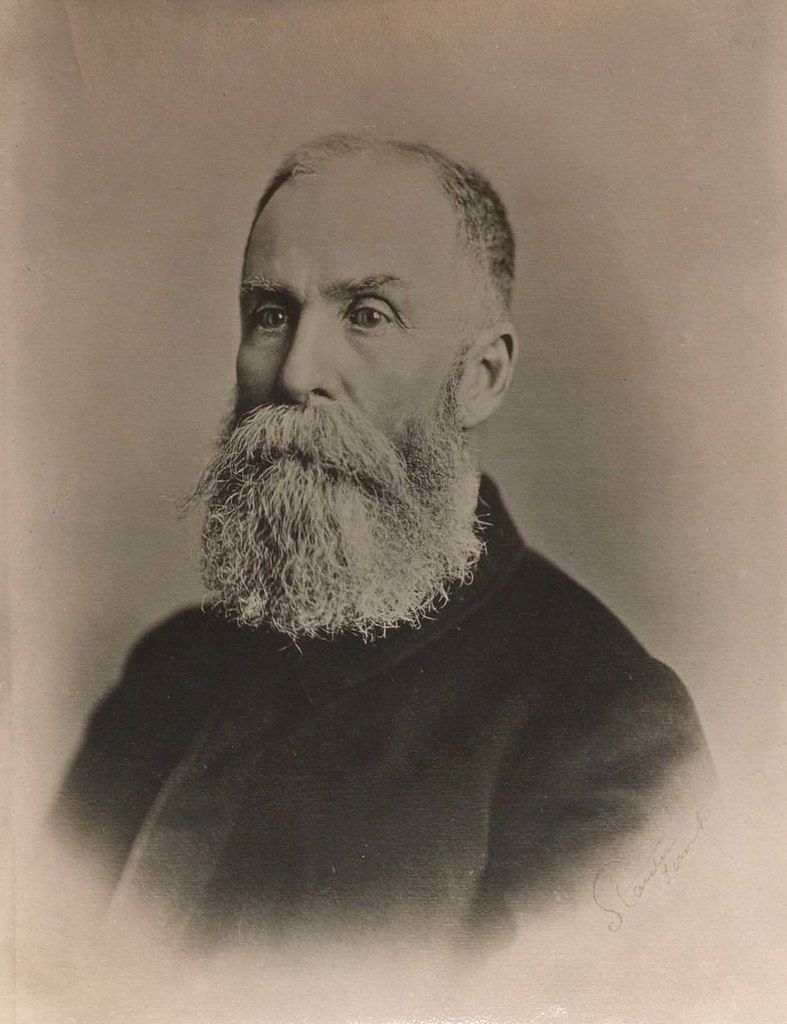

James Bovell (1817-1880)

The first milk injection into a human occurred in Toronto in 1854 by Dr. James Bovell and Dr. Edwin Hodder. They believed that oily and fatty particles in milk would eventually be transformed into “white corpuscles,” or white blood cells. Their first patient was a 40-year-old man whom they injected with 12 ounces of cow’s milk. Amazingly, this patient seemed to respond to the treatment fairly well. They tried again with success. The next five times, however, their patients died.

Despite these poor outcomes, milk transfusion became a popular method of treating the sick, particularly in North America. Most of these patients were ill with tuberculosis and, after receiving their blood transfusions, typically complained of chest pain, nystagmus (repetitive and involuntary movements of the eyes), and headaches. A few survived and, according to the doctors carrying out these procedures, seemed to fare better after the treatment. Most, however, felt comatose and died soon after.

Experiments and Revelation

Most medical treatments today are tested on animals and then on humans, but this process was reversed for milk transfusions. One doctor, Dr. Joseph Howe, decided to experiment to see whether milk or some other factor was causing these poor outcomes. He bled several dogs until they passed out and attempted to resuscitate them using milk. All of the dogs died.

However, Howe would conduct another experiment in milk transfusion, believing that the milk itself wasn’t responsible for the dogs’ deaths but rather the large quantity of milk he had administered. He also eventually hypothesized that using animal milk — he sourced it from goats — in humans was causing adverse reactions. So, in 1880, Howe gathered three ounces of human milk to see whether animal milk was incompatible with human blood.

He transfused this into a woman with a lung disease, who stopped breathing very quickly after being injected with milk. Fortunately, Howe resuscitated the woman with artificial respiration and “injections of morphine and whiskey.”

Legacy and Modern Insights

By this time, around 1884, the promise of milk as a perfect blood substitute had been thoroughly disproved. By the turn of the century, we had discovered blood types and established a safe and effective method of transfusing blood. Would these discoveries have occurred without the dodgy practice of injecting milk into the bloodstream?

It’s difficult to say. At the very least, we can confidently say that life is much better—less hairy—for sick people in the 21st century than in the 19th.

References

- “Transfusion Of Milk.” Accessed 12 Mar. 2024. The British Medical Journal, vol. 1, no. 954, 1879, pp. 557–59. JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25250674.

- 19th-century medicine: Milk was used as a blood substitute for transfusions [Internet]. Accessed on March 12, 2024. Available from: https://bigthink.com/health/milk-transfusion/

About Docquity

If you need more confidence and insights to boost careers in healthcare, expanding the network to other healthcare professionals to practice peer-to-peer learning might be the answer. One way to do it is by joining a social platform for healthcare professionals, such as Docquity.

Docquity is an AI-based state-of-the-art private & secure continual learning network of verified doctors, bringing you real-time knowledge from thousands of doctors worldwide. Today, Docquity has over 400,000 doctors spread across six countries in Asia. Meet experts and trusted peers across Asia where you can safely discuss clinical cases, get up-to-date insights from webinars and research journals, and earn CME/CPD credits through certified courses from Docquity Academy. All with the ease of a mobile app available on Android & iOS platforms!